The Present

2012

the present I

c-print

26,0 x 33,0 cm

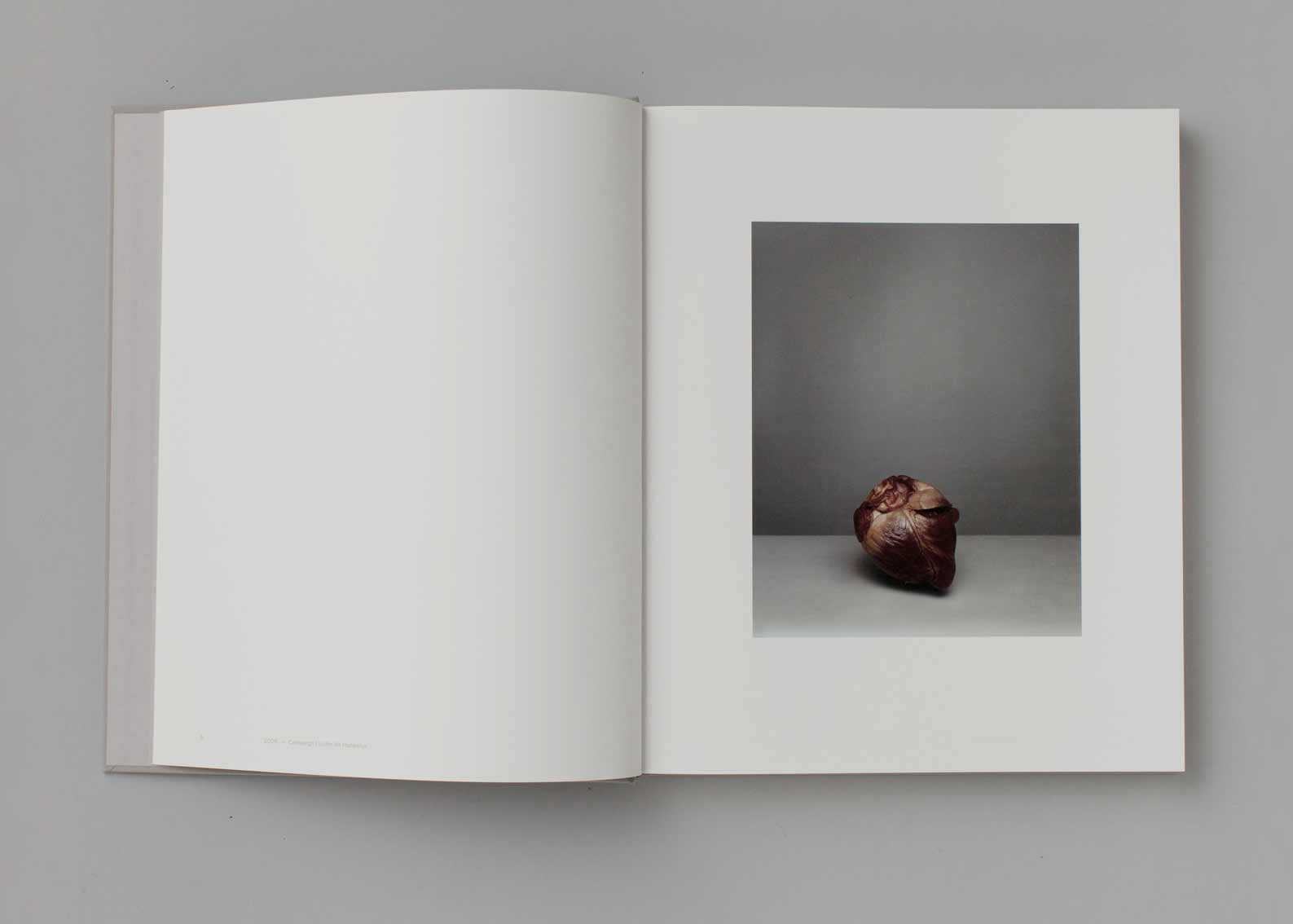

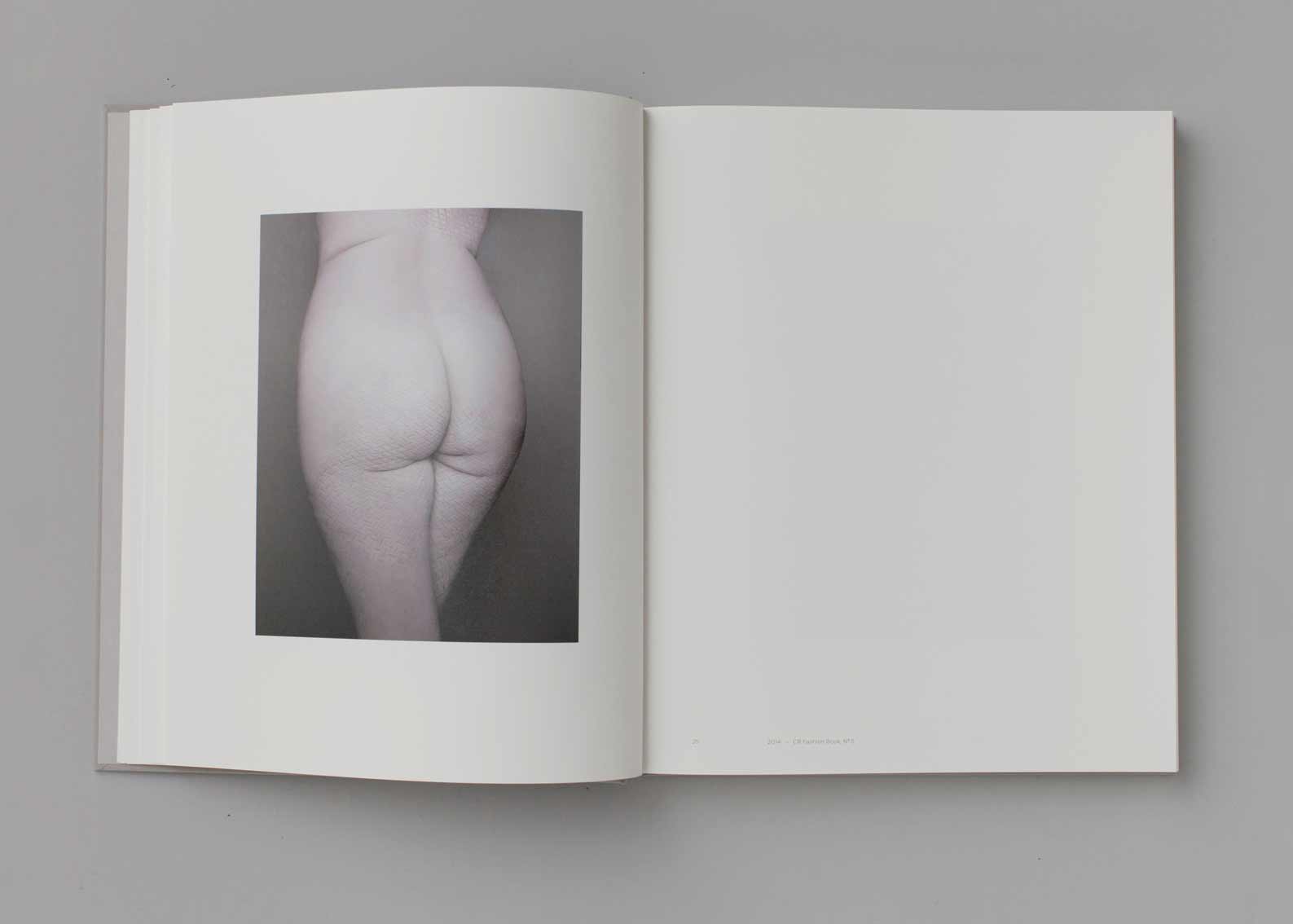

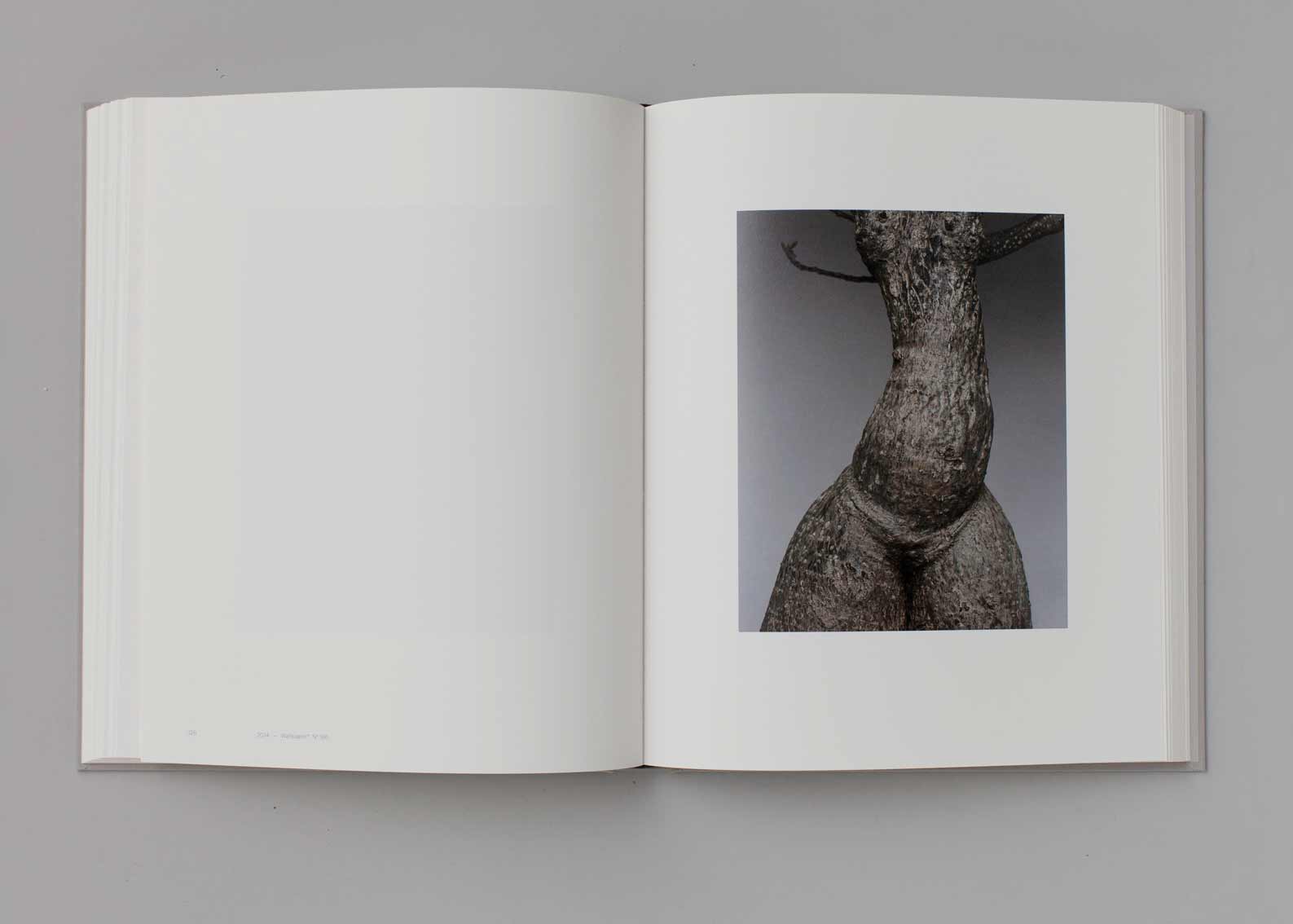

ECCEHOMO.

The Body as the Place of Memory

Brigitte Niedermair portrays the mummy of the Val Senales Glacier by moving away from the display site and the actual body preserved in a controlled environment in compliance with scientific criteria, in order to sublimate it until it becomes the imaginative representation of the body.

The title “eccehomo” was chosen by the artist herself, who uses the words of Pontius Pilate to point a finger at the human body, the temple of memory in which all of life is preserved, and can be consulted, just like in a book. Body as memory, as biographical code. In cultural history, the imaginative representation of the body vaunts a long tradition, which sinks its roots into Antiquity and extends throughout the Middle Ages. Against oblivion, here is the metaphorical body. In her photographic works, Niedermair takes the body apart, saving only some of the details in that they are the fragments of an icon. The detail represents the whole, the idea of the body is, after all, indivisible, and yet it is fractionable for the gaze. Particles for the whole. The gaze placed on the feet of the Man who came from the ice manifests analogies with the Passion of Christ. If, on the one hand, the wounds caused by the nails are missing, associations with references from Western iconography soon become evident. The skin especially plays the role of man’s visual and tactile memory. It is the skin that preserves just how much it was, and is, biographically real. The skin becomes a metaphor for life. If for medieval religiosity the gaze upon the body of Christ was an instrument used to purify the eye, then the gaze upon the body of Man captures the person’s symbolic image. The mummy becomes the symbol of a part for the whole, the metaphor for man and his genetic and historical evolution. The fact that the gaze falls upon the body of a man, which does not appear to show any visible signs of death, but is, rather, captured in an instant lasting millions of years, may have convinced Brigitte Niedermair to portray the Adam-Ötzi as the only person to capture in an image. No portrait could be more powerful. Its body exudes an aura that strikes the viewer and leaves a deep mark. The photograph of the Man who came from the ice occupies the entire exhibition room. The three-dimensional body becomes, in its two-dimensional representation, the viewer’s “skin”. It is the body that envelops. Those to which this process is addressed thus find themselves inside an experiential media ambient, which transforms the self of the viewer into an “object” before an “object”. Is is the “subject” before the “subject”. Indeed, in her photographs Brigitte Niedermair does not portray reality, that would be too banal, too simple. Her works move upon a sophisticated border, calling into question every aspect of reality.

The image hypertrophies the reality, which, like the shadows of Platonic memory, becomes hard to identify. The alienating effect does not start from the image, but from the viewer. And this also happens when we observe the cycle “eccehomo”, a sequence of carefully pondered images, which casts a new gaze upon the individual, at a rhythmically regular cadence. At this moment in time, there is no difference between imagining the mummy or elaborating what was viewed in its visual perception. The pretense of photography is intrinsic to its idea of itself, as material that is transformed by the gaze. Niedermair, in all her creative jargon, manifests herself within it. And what about memory? Is it elevated from the biographical matrix of the body? Is it made legible by the elementary tracks of life, transforming itself into a genus of the human? The photographic images do not offer a definitive response, all that is evident is the impression left by life on the corporeal object. Like a vision, the gaze upon the body is subtracted from concrete time. From the finished past emerges the future. The study of “eccehomo” can be interpreted as a prayer. A prayer that aims to suspend the traditional categories of human existence.

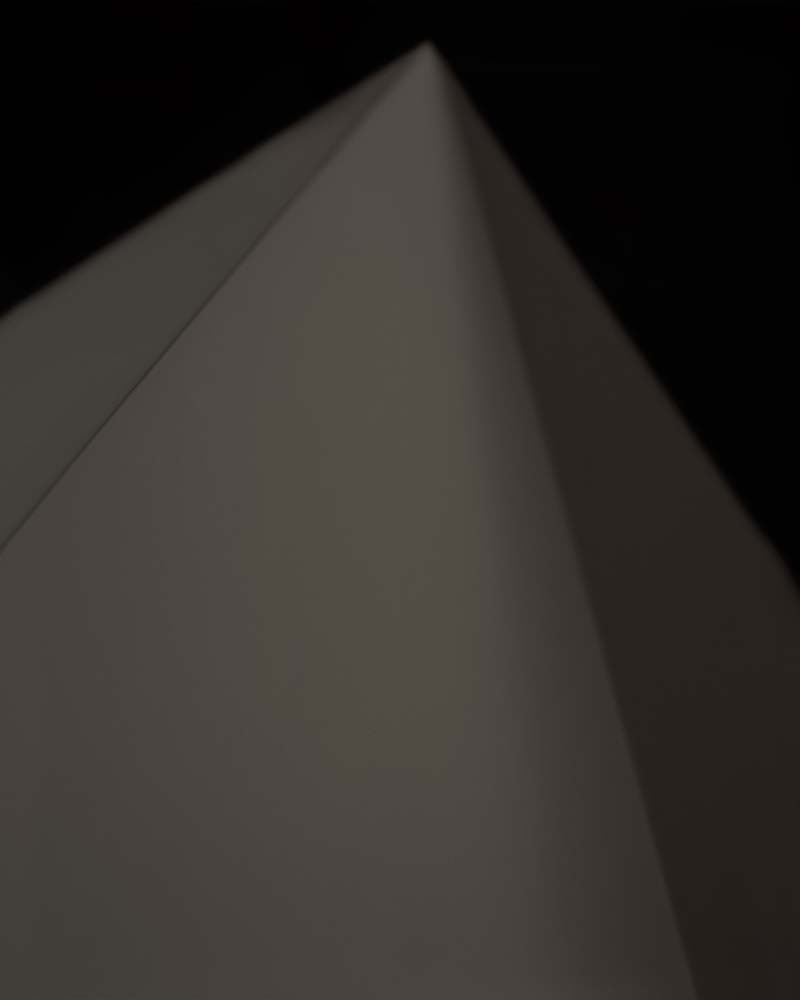

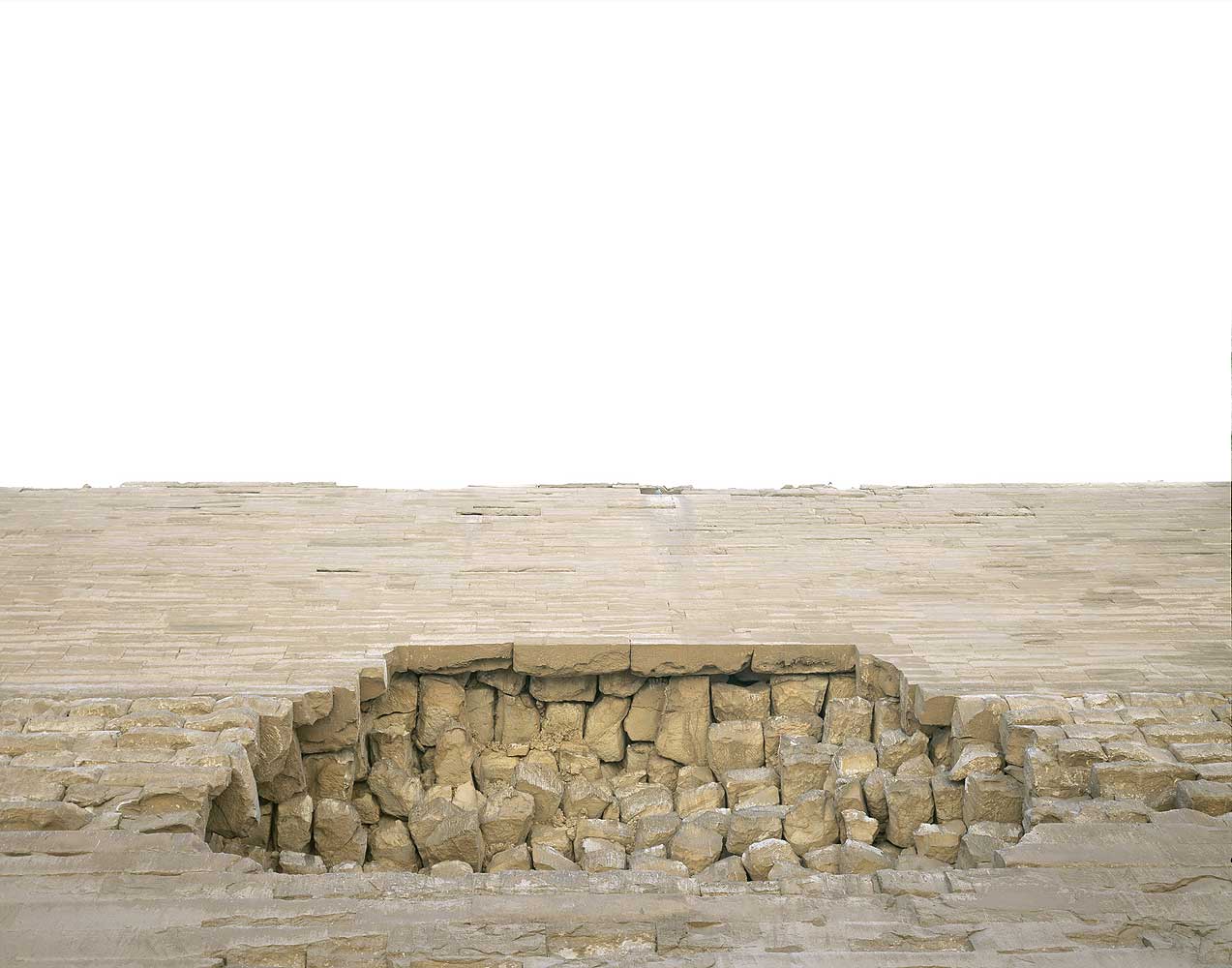

ARE YOU STILL THERE

The work are you still there concentrates on one of the largest works of funerary architecture in history: the pyramids of Egypt, monumental and extraordinary constructions that are a symbol of the passage between this life and the next. Brigitte March Niedermair’s research, carried out from 2011 to 2014, after arduous and complex investigations in Egypt, probes the horizon of the pyramids, a mysterious boundary between earth and sky, between visible and invisible. In some photos this seems to have faded, to have become almost impossible to find. Heaps of stones, piled up after the collapse of the pyramid, trace lines with sinuous forms that symbolically represent the point of transition between the material and the spiritual world.

With her view camera always pointed at the sky, at Saqqara, Abusir, Dahshur, Meidum, Hawara and el-Lahun, Niedermair went in search of the horizon of these mysterious constructions, as if wishing to investigate the line that separates life from death, the very fine line that marks the point of division, according to Egyptian mythology, between Nut, goddess of the sky, and Geb, god of the earth.

In an extremely refined photographic operation, the artist presents her personal vision of the pyramids, explored from a completely new viewpoint, showing us images that do not speak of monuments and architectural complexes, but of spirituality and energy, of the quest for the inner and secret horizon that runs through the existence of each one of us.

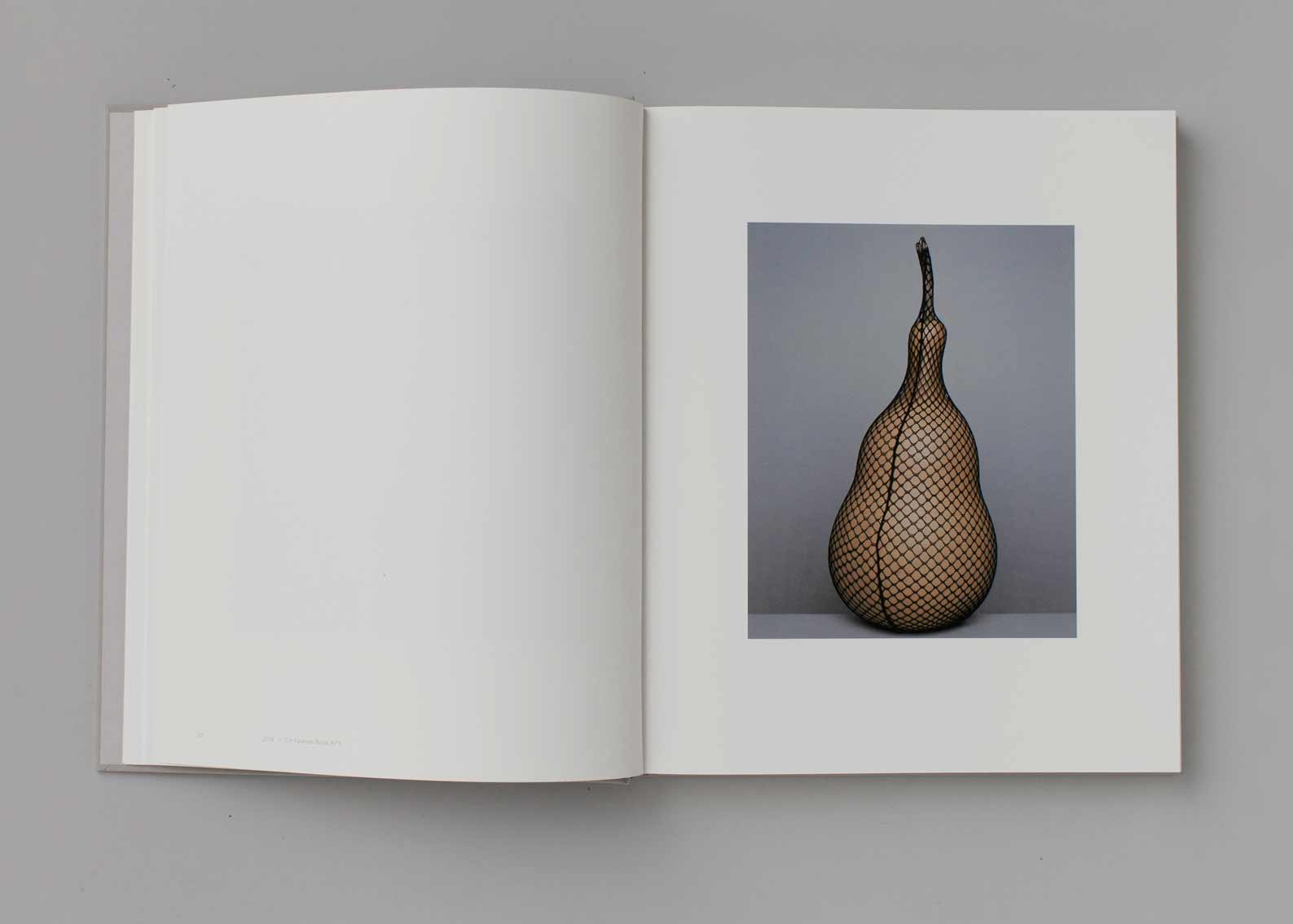

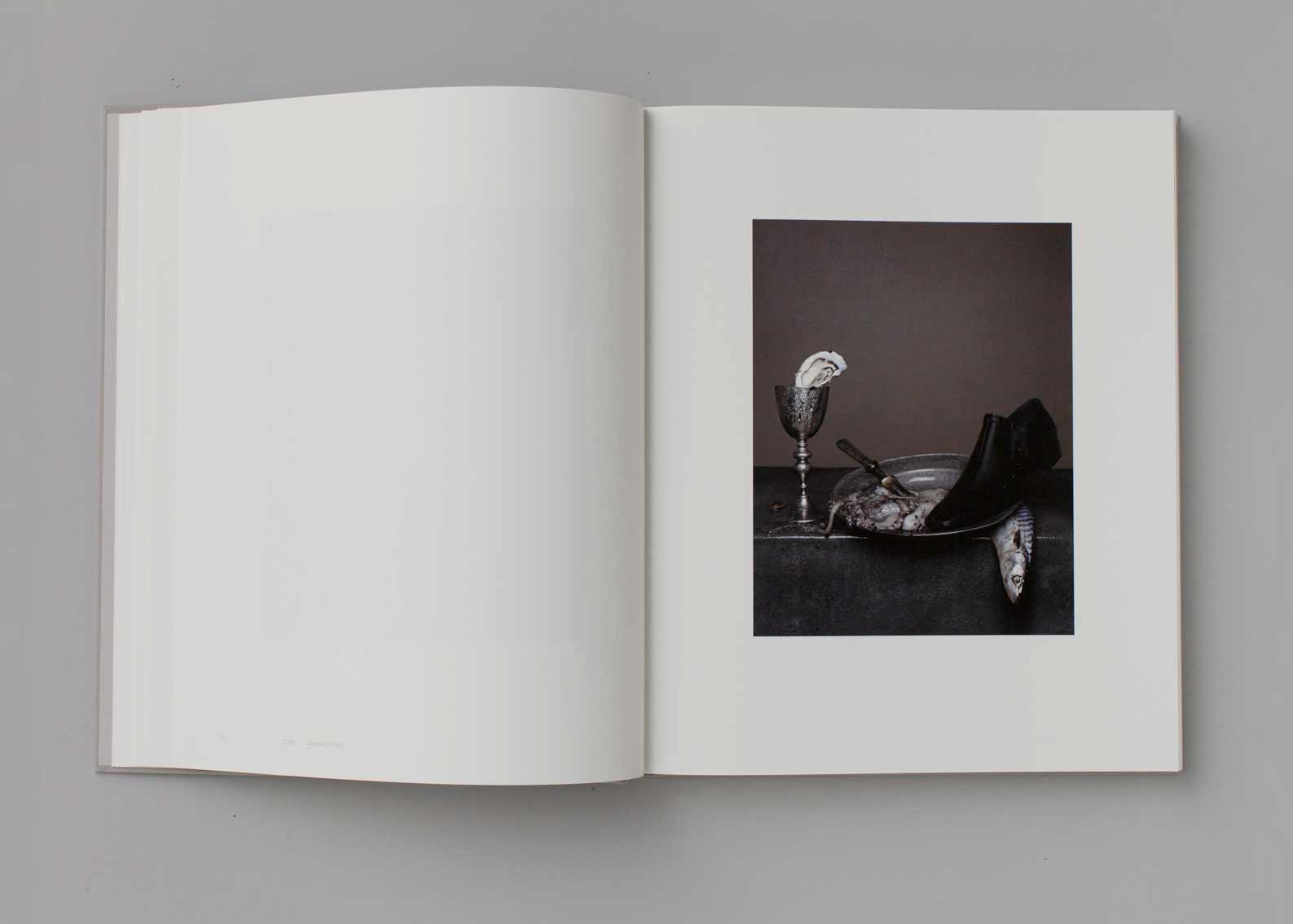

TRANSITION_GIORGIO MORANDI

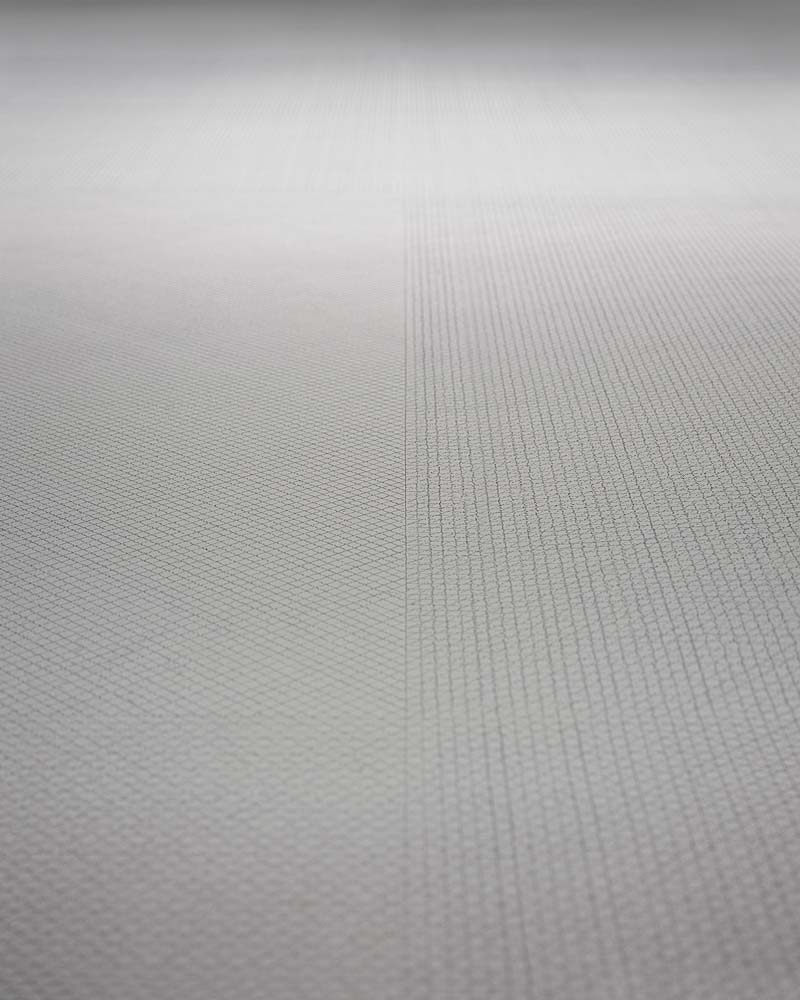

The series of photos Transition_Giorgio Morandi (2012-13) starts out from a reflection on the painting of Giorgio Morandi and his ability to speak to us about an open universe, one that goes beyond the dimension of the individual object and poses continual questions rather than providing answers. Through the eye of her camera Niedermair has taken a close look at the objects in the artist’s studio, in an attempt to understand the tensions, the emotions and the complexity of his apparently simple still lifes.

“I wanted to see through his eyes, to feel the same emotional tensions, chase after his forms and put myself to the test by literally using his objects in the space, which is nothing but a mental space.” With these words the artist from Alto Adige explains the origin of her project, in which she went many times to the studio on Via Fondazza, entering into intimate relationship with Morandi’s models. She spent whole days peering at them with her lens, with respect and modesty, taking blurred pictures in which the only element in focus is the sharp and clearly defined line of the horizon, i.e. of the plane of composition, as if it were an inner horizon, a metaphor for an open universe in which to lose oneself in order to find nothing but the essential. The object, in Brigitte’s photos, loses the significance that it has in Morandi’s works; it is no longer a pretext to mull over the formal and geometric aspects of the composition, but becomes a mysterious presence that at a certain point even disappears to leave room just for the horizontal line, the ultimate limit to which we can push our vision, symbol of a human space in continual motion, but always in equilibrium.

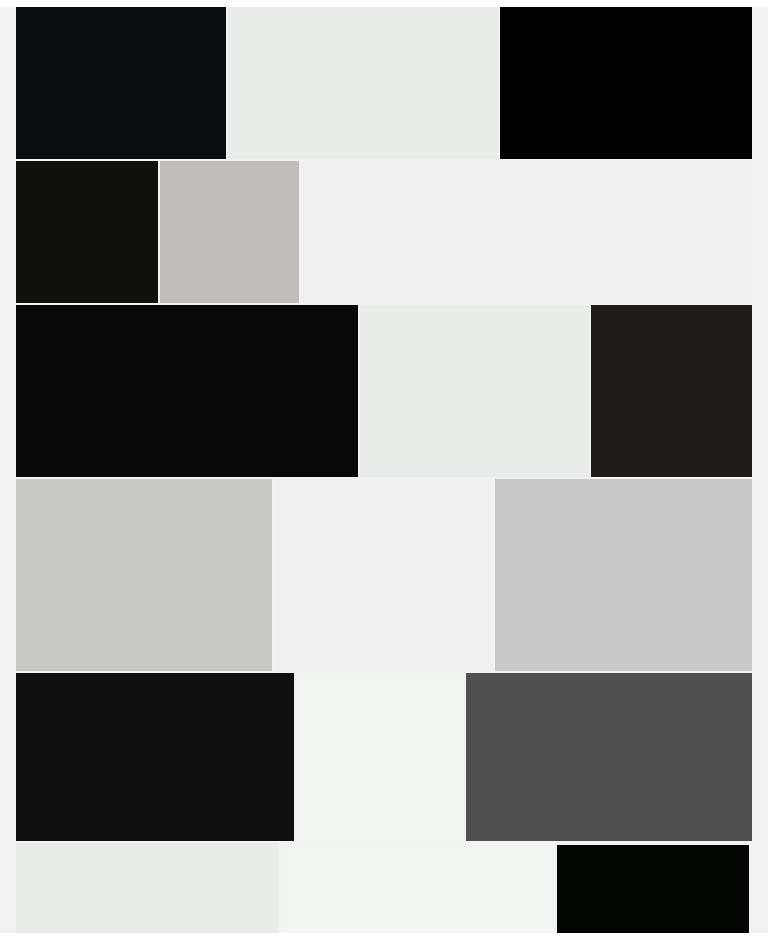

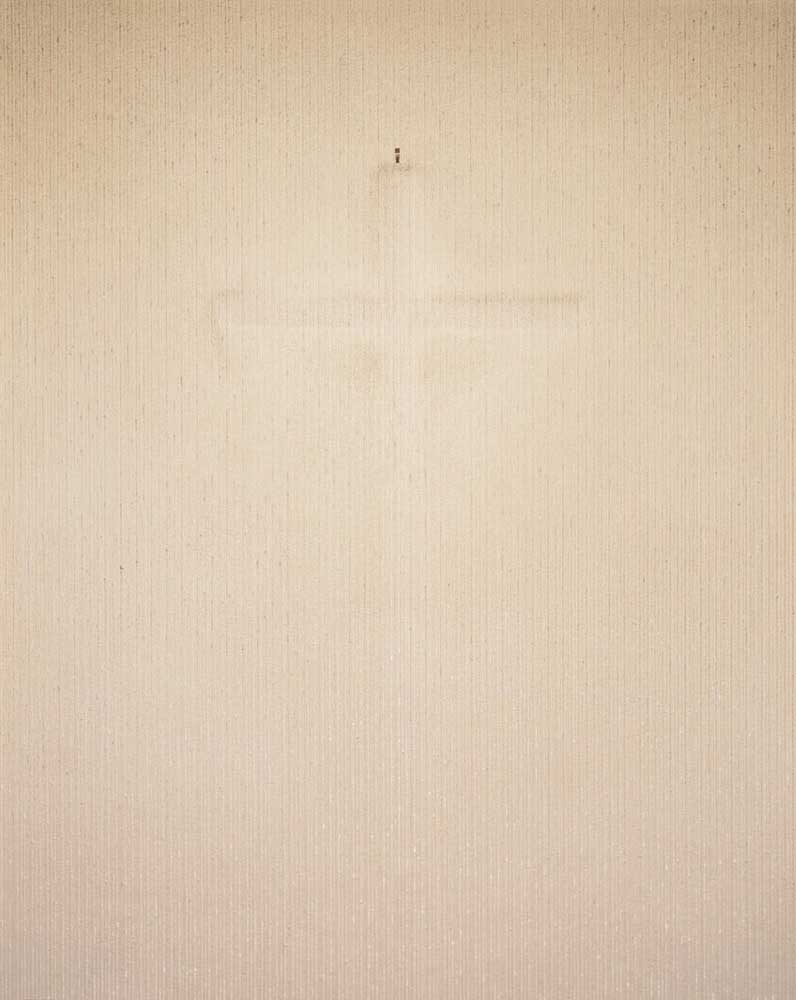

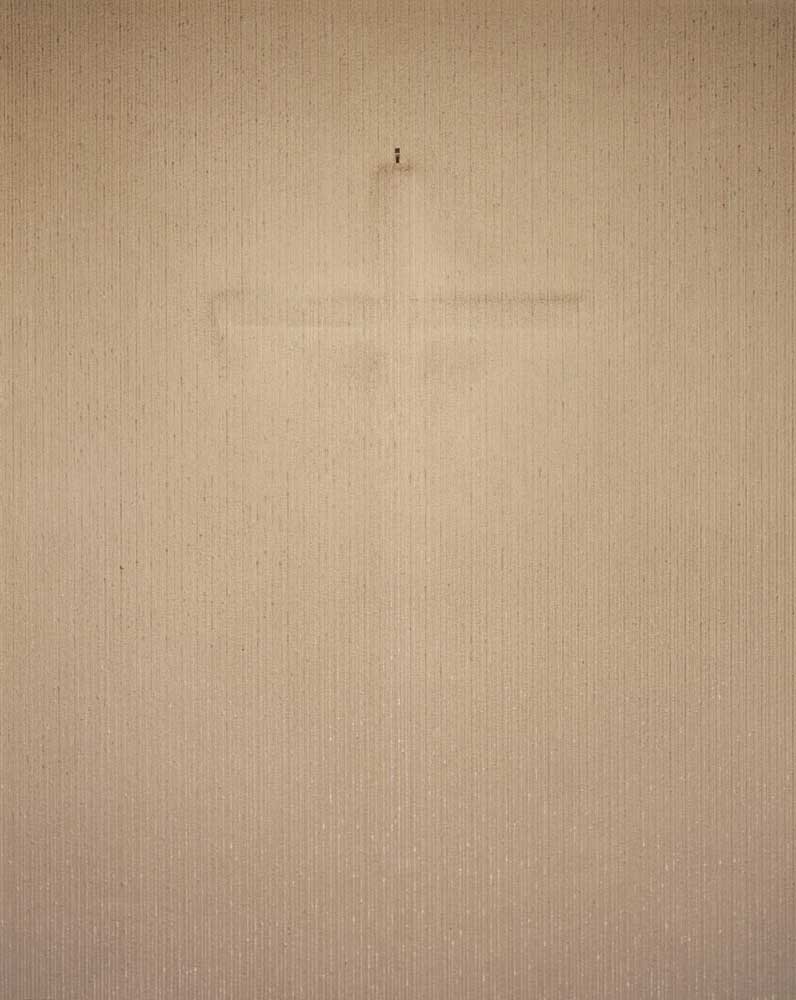

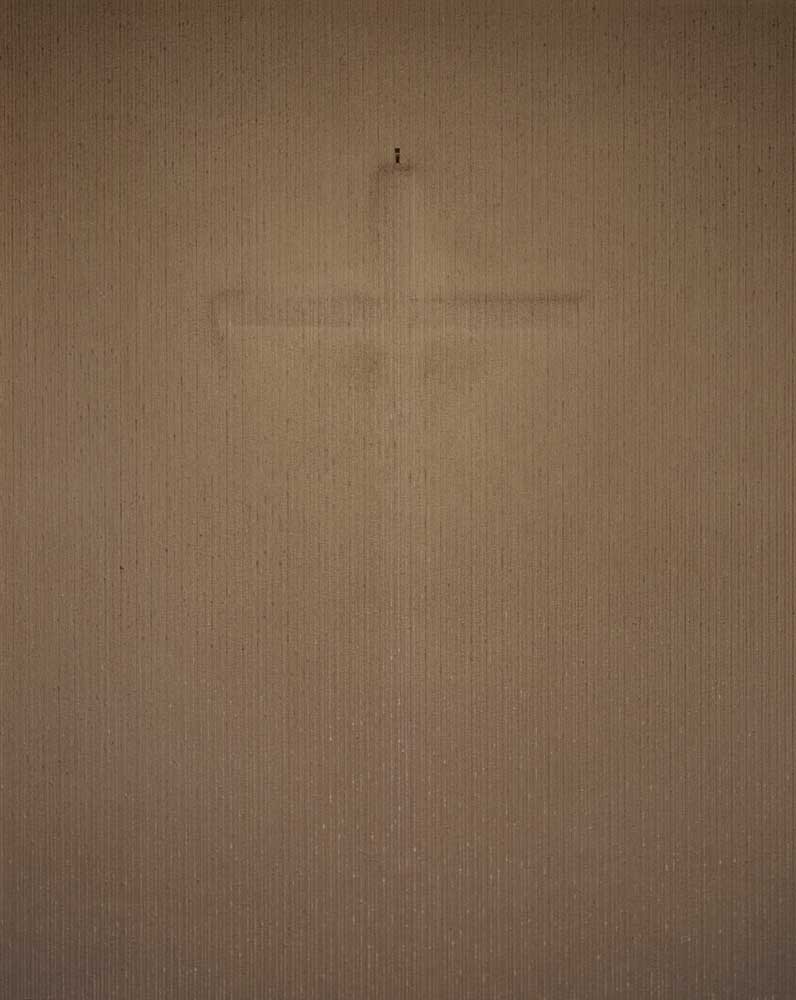

DUST

Dust marks the beginning of this new period of research. It is no coincidence the work was conceived at the same time that the artist experienced the birth of her child. The symbol of the cross appears as a trace in the dust, inducing us to reflect deeply on life and death as well as suffering as a moment of catharsis and regeneration. The photographic sequence informs our understanding, from darkness to light, in a circular process.

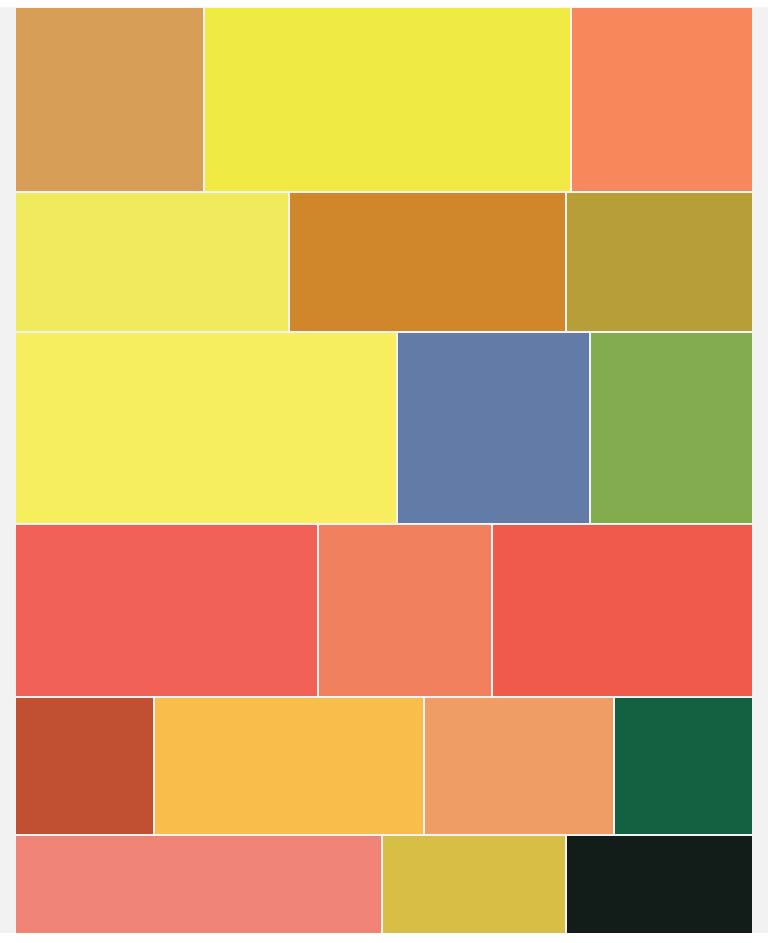

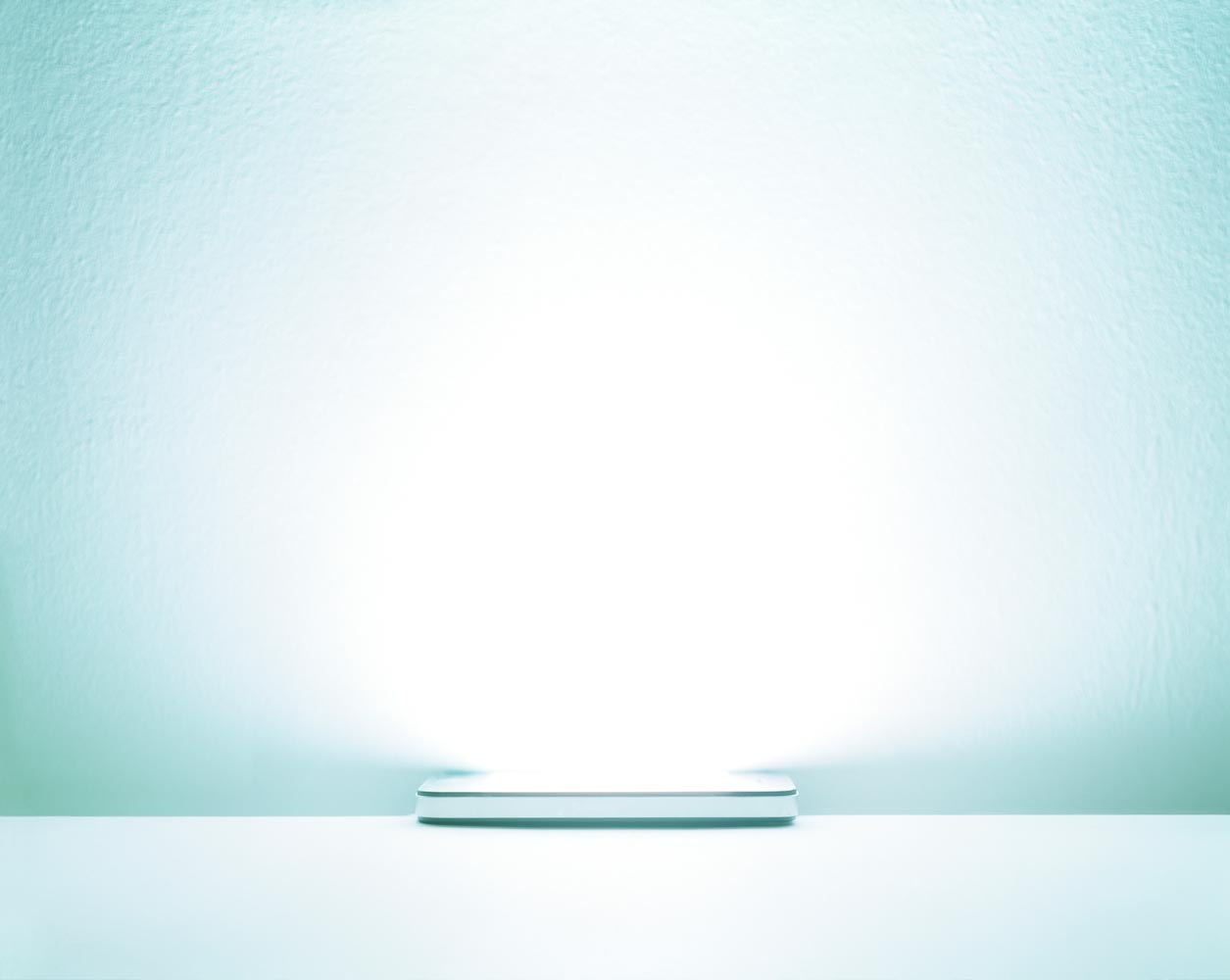

THE PRESENT

The Present is an introspective moment of great intensity on the significance of the present time. The iPhone is an object from which to transcend; to find a rising sun and a primeval fire, but also the light of the contemporary world. Both present and past find a precise location in a single point. The photographic sequence leads our eye towards abstraction.

EDEN

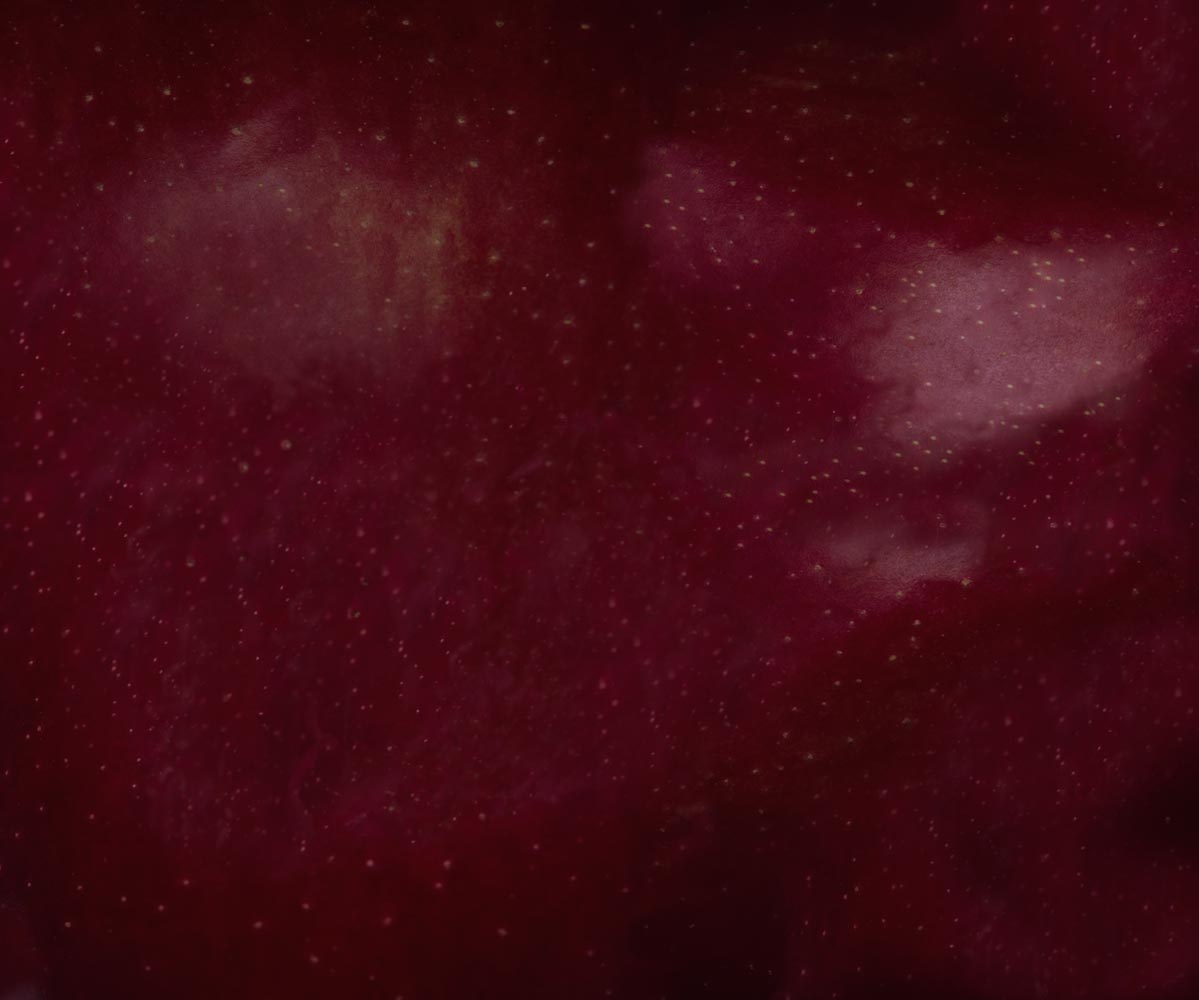

Eden communicates an apparition, a vision of a starry sky, all based on the random observation of an apple. Niedermair's eye focuses insistently on the object, delving so deeply into the detail as to modify our perception of it, bringing about a degree of abstraction that generates figures which are images of infinity.

SCREENSHOT

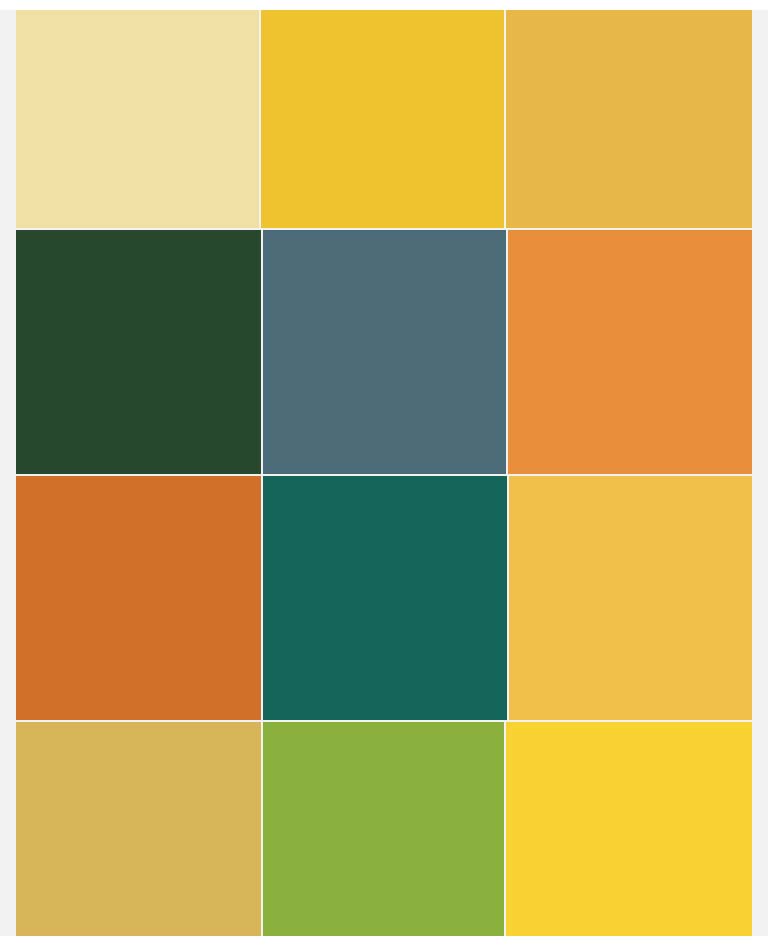

In 2017, Brigitte Niedermair and Martino Gamper

were the protagonists of Screenshot - created for the 40th anniversary

of DEDAR and curated by Helen Nonini. It was a conceptual reflection

that reinterpreted the great history of art through the medium of digital

technologies.

The idea stemmed from a eureka moment from Martino Gamper and

Brigitte Niedermair. On a car journey, the designer and the artist were

attempting to download an image from the browser on their

smartphone at a time when the network signal was particularly weak:

due to this “technological limit”, the image they were looking for (a work

from Picasso’s blue period) appeared as an abstract composition,

composed of a series of coloured geometric figures. It was a true

revelation: the symbolic and unexpected digital synthesis of certain

masterpieces, powerful fragments of memory from art history.

Hence the idea of conducting a specific exploration into colour,

specifically blue, using the screenshots as the basis: the resulting

patterns are printed onto high-quality DEDAR fabrics and become wall

panels that straddle art and experimentation, uniqueness and seriality.

Nina Yashar is fascinated and struck by the innovative language of

design and, realising the great expressive potential, decides to bring it

back to life - also thanks to the partnership with Helen Nonini - creating

even more innovative and engaging design applications.

The gallery owner therefore made a proposal to the artist and the two

designers to create a total Screenshot, where the work of art turns into

design and takes centre stage - in both functional and aesthetic terms -

in an evoking and powerful interior design project.

Thus began a new creative process exploring the art of the minimalist

period - Sol Le Witt, Carle Andre- but reinterpret also the works by Otto

Dix, Caravaggio or Paul Klee - giving rise to elegant abstract patterns

that become curtains, carpets and wall coverings and gallery

furnishings, in a dreamlike colour chart that straddles concept and

function, art and design.

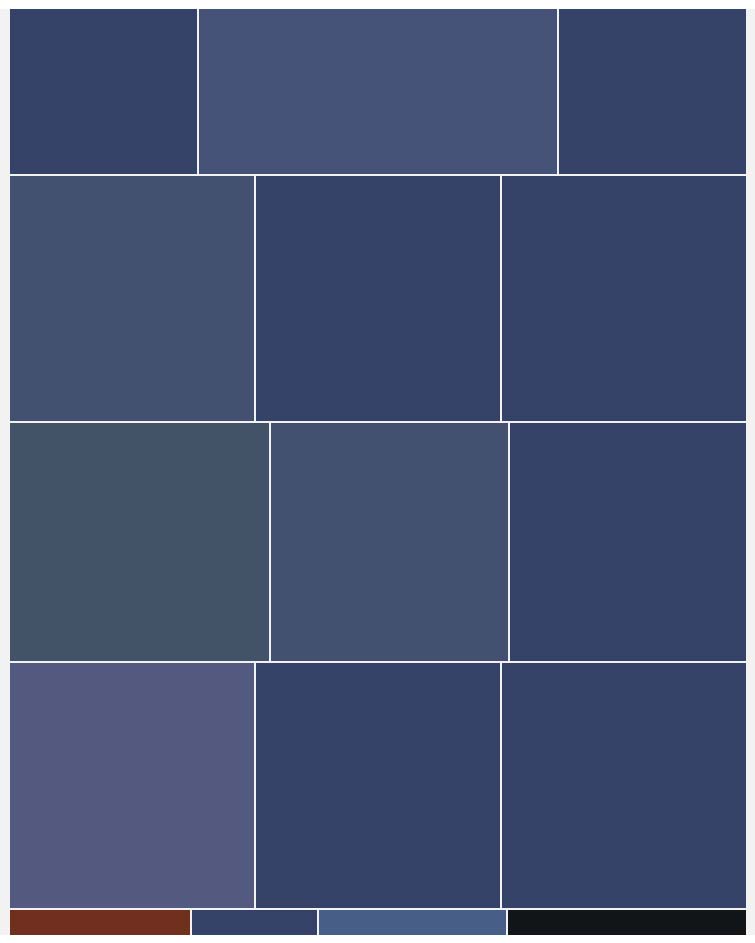

SOL LEWITT

Doing, Waiting, Seeing

Jordan Stein

exhibition? How might she free the work from its intimate relationship with the architecture? If her initial investigations bore fruit, she advised the foundation, she would share them. “You always have to find the door,” she told me.

Niedermair brought a ruler on her first visit to the Foundation. Like an astronomer training her telescope on the night sky, she was

looking for a spark. She had always thought, as many do, that LeWitt’s output was cold and impersonal — best to meet it on its own terms,

with numbers. She kept biographical and artistic research to a minimum in order to see the exhibition as freshly and indiscriminately as

possible.

Time after time, she measured the space between pairs of LeWitt’s lines at 10.5 centimeters. Double it, she intuited, and that made

21, a new ruler. And so it began, a journey though the exhibition, the center of her lens fixed at exactly 21 centimeters from the object of

her camera’s gaze. Within the quantifiable system she had designed, there were suddenly infinite possibilities to explore. The ruler was a

skeleton key that granted access to all manner of door.

Her commitment to 21 centimeters also freed the project from the terrifying — and very real — possibility of aestheticizing the

extraordinary installation. She was hoping to make an impression, not a document. If Between the Lines sought “to move beyond the

division that traditionally separates architecture and art history,” as indicated by the Foundation’s press release, Niedermair’s project

aimed to move beyond the division that traditionally separates artwork from its record.

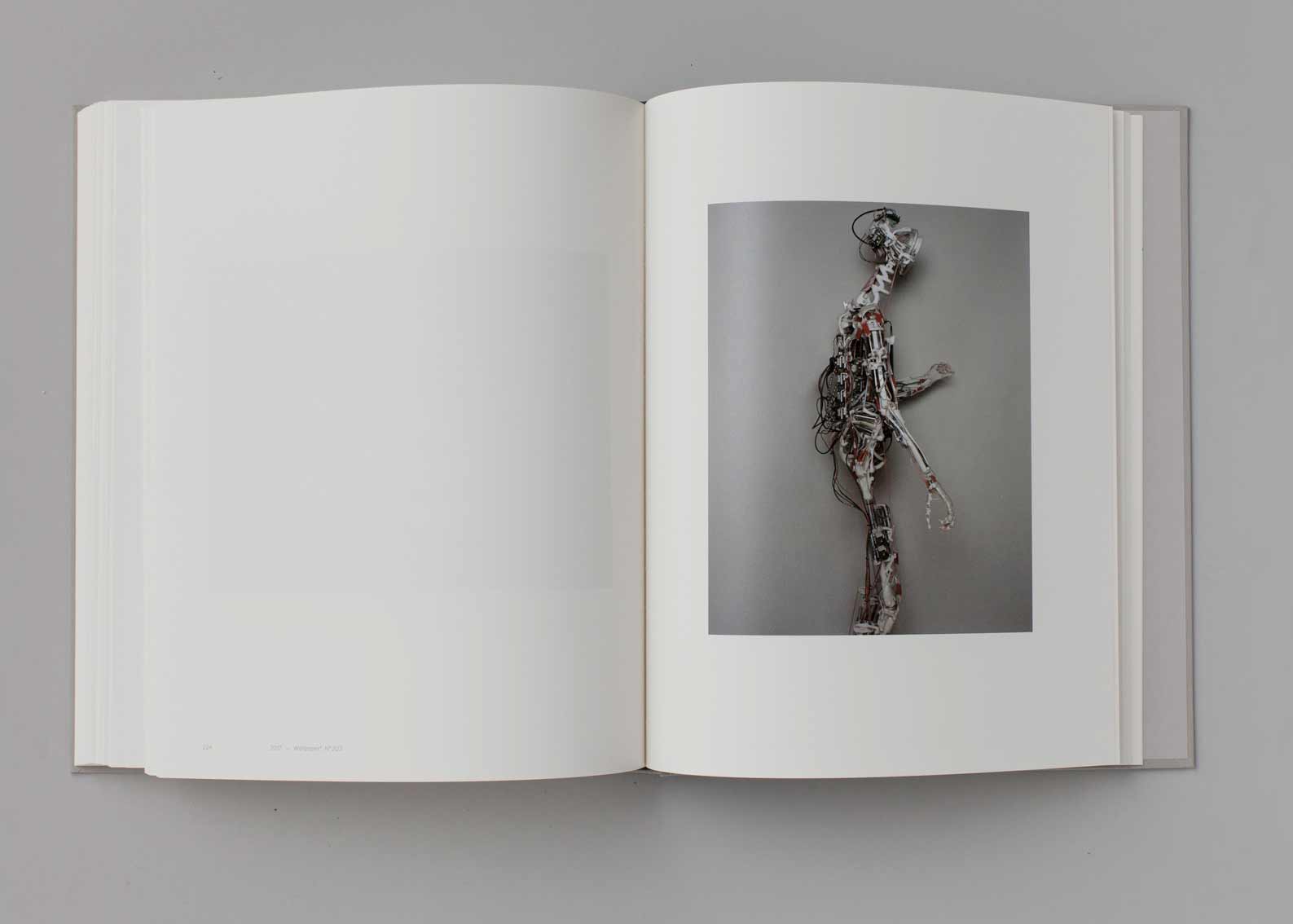

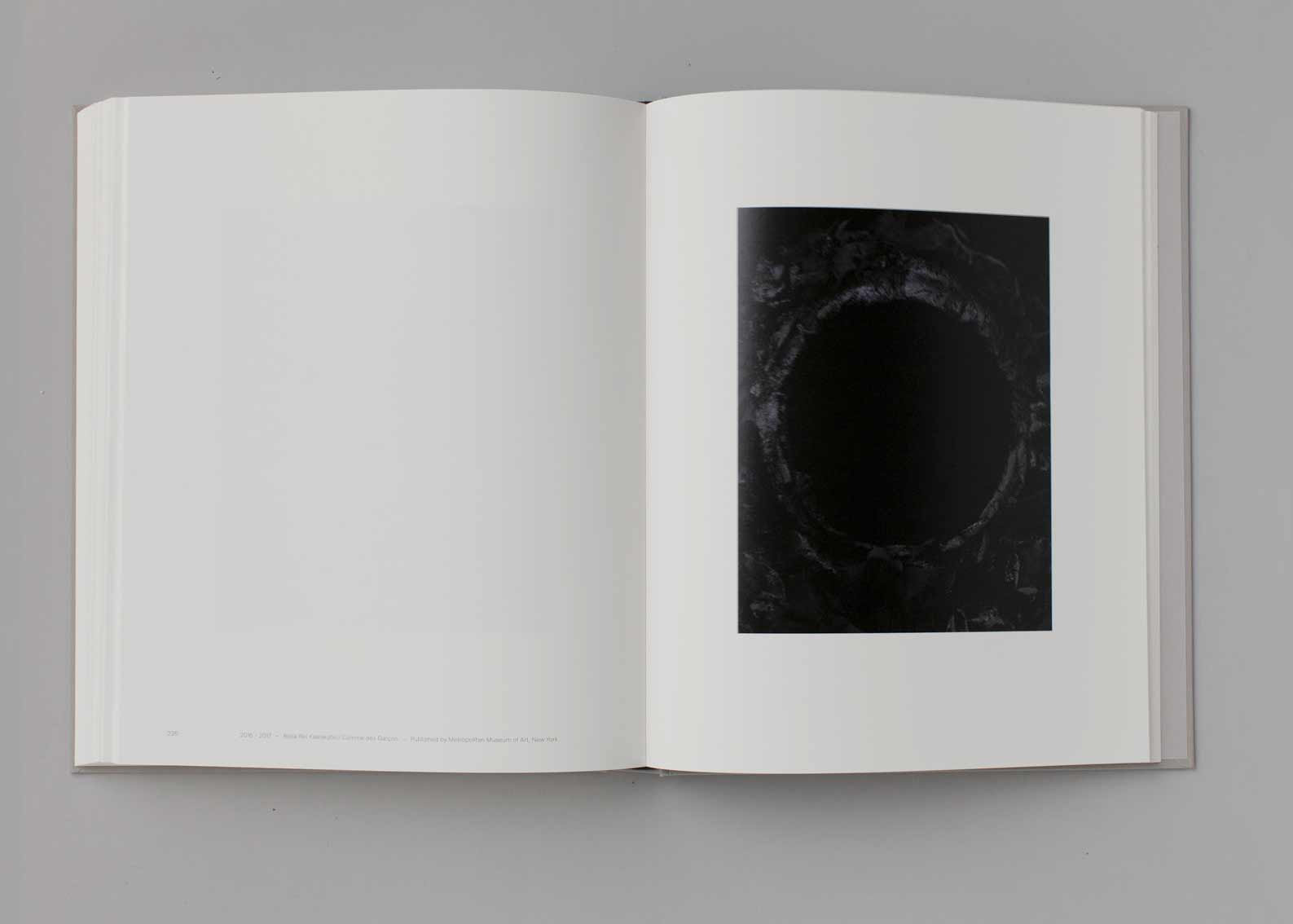

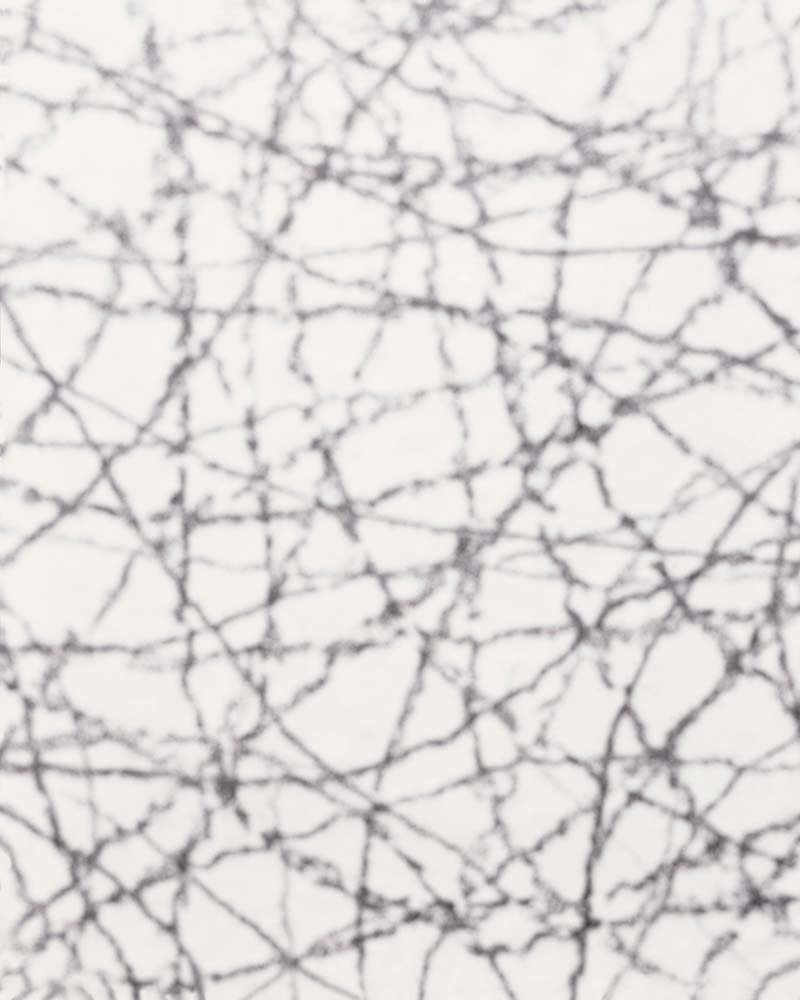

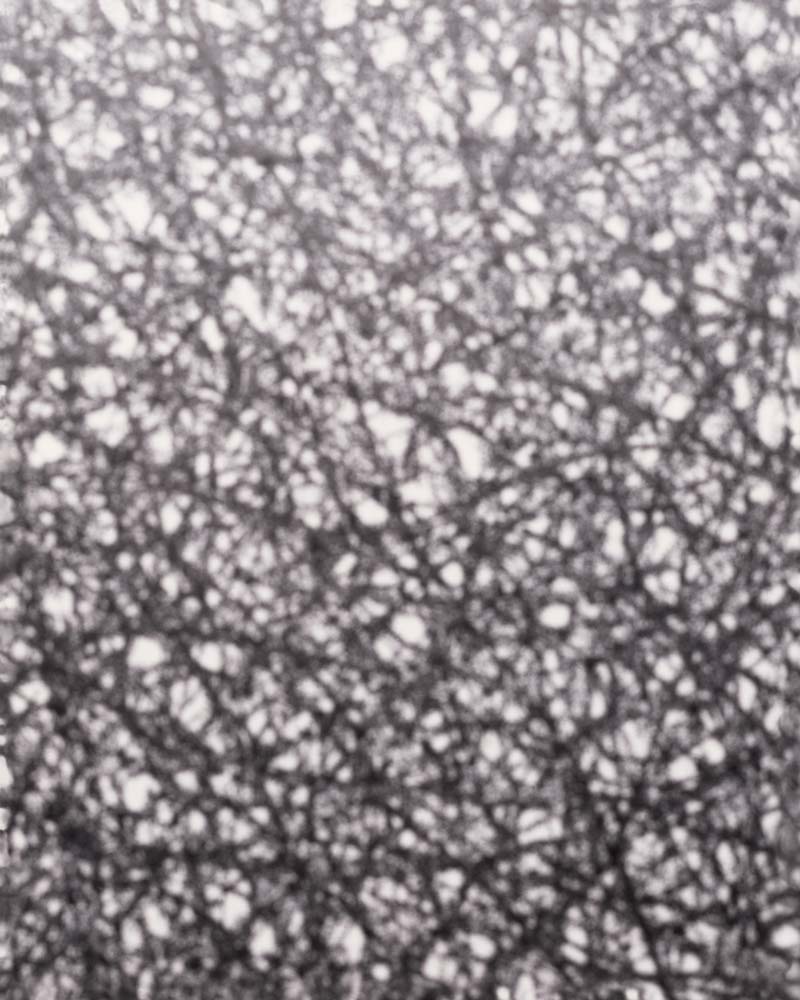

The book begins abruptly, with a journey through time and space. The image recedes, mostly in black, to conjure a time warp, a

portal, and outer orbit — it immediately establishes an evidence-based photographic quest for the immaterial. Notably, the image is a

touch off balance, indicating the fallibility and humanity at the heart of her efforts. The form depicted also happens to resemble the tall,

mysterious, and rectangular insides of a 4 x 5 inch camera, Niedermair’s principle recording device.

From there, and page after page, we find abstracted bits of LeWitt’s work transformed into a poetical panorama of the natural world

— dendrites, wind patterns, horizons, eclipses, trees, crystallography, and more. Perspective and scale, the bedrock of proper exhibition

photography, are uprooted as Niedermair’s camera alternately plays the role of microscope, satellite, and scanner.

One of LeWitt’s great gifts was to transform two dimensions into three dimensions with exceptional efficiency, a power Niedermair

understands and exploits. Her analytical strategy gives way to an emotional resonance as the camera animates the insides of his work.

To this end, many of the photographs blur the surfaces of their ostensible subjects, moving beyond clearly defined form and rendering

walls, ceilings, and floors irrelevant.

Niedermair distills this idea with a pair of leaning and irregular black and white monoliths (photo 22). The questions posed by the

twin images are so powerful as to initially sound foolish: Are we looking at something or nothing? Objects or blank spaces? Presence or

absence? At or through? Somehow, impossibly, we’ve arrived at a shimmering uncertainty just beyond the perceivable.

Spiritual preoccupations are nothing new to art, but it’s worth noting that the secret, hidden, or otherwise invisible are experiencing

something of a mainstream resurgence in the world of art. Unexpectedly, the implications of Niedermair’s project unexpectedly tease out

the metaphysics present in even LeWitt’s most conceptual works. The life cycle of a wall drawing, for example, ends with a fresh coat of

paint rather than de-installation, transportation, or conservation. The work is never stored, but simply exists until the moment it ceases to

exist. What, after all, is more metaphysical than an idea alive in the world, the eyes, and the mind?

A touch of the mystical is embedded in Niedermair’s use of the 4 x 5 inch camera, a cumbersome, expensive, and risky instrument to

recruit. The film requires several days to process and review once it’s exposed. With this in mind, the artist described her practice to me

with three words: “Doing, Waiting, Seeing.” This, of course, is in stark contrast to the extraordinary collapse of time endemic to most

contemporary image-making in which the doing is the seeing, and waiting simply doesn’t exist. It is critical that her work is made slowly

and deliberately.

The book concludes with an oblique self-portrait, both in and out of focus. An irregular black diamond holds a hazy reflection at its

center. Somewhere in the darkness, circular points of light make a spotty halo, slowly revealed as the outline of the camera lens. The

image acknowledges the technology that made Niedermair’s investigation possible and affirms our dependence on tools to make sense

of the worlds around and inside us. Brigitte Niedermair had not only found the door, but walked right through it.

1 ⁄ Artforum, Summer 1967, Vol. 5, No. 10

MADAME HIRSCH

“Once an object of wonder because of its capacity to render reality faithfully, as well as despised at first for its base accuracy, the camera

has ended by effecting a tremendous promotion of the value of appearances. Appearances as the camera records them. Photographs do

not simply render reality-realistically. It is reality which is scrutinized and evaluated for its fidelity to photographs. […] Instead of just

recording reality photographs have become the norm for the way things appear to us, thereby changing the very idea of reality, and of

realism.”

Susan Sontag, from the essay “The Heroism of Vision”, On Photography, Penguin, London, 1979, p. 87

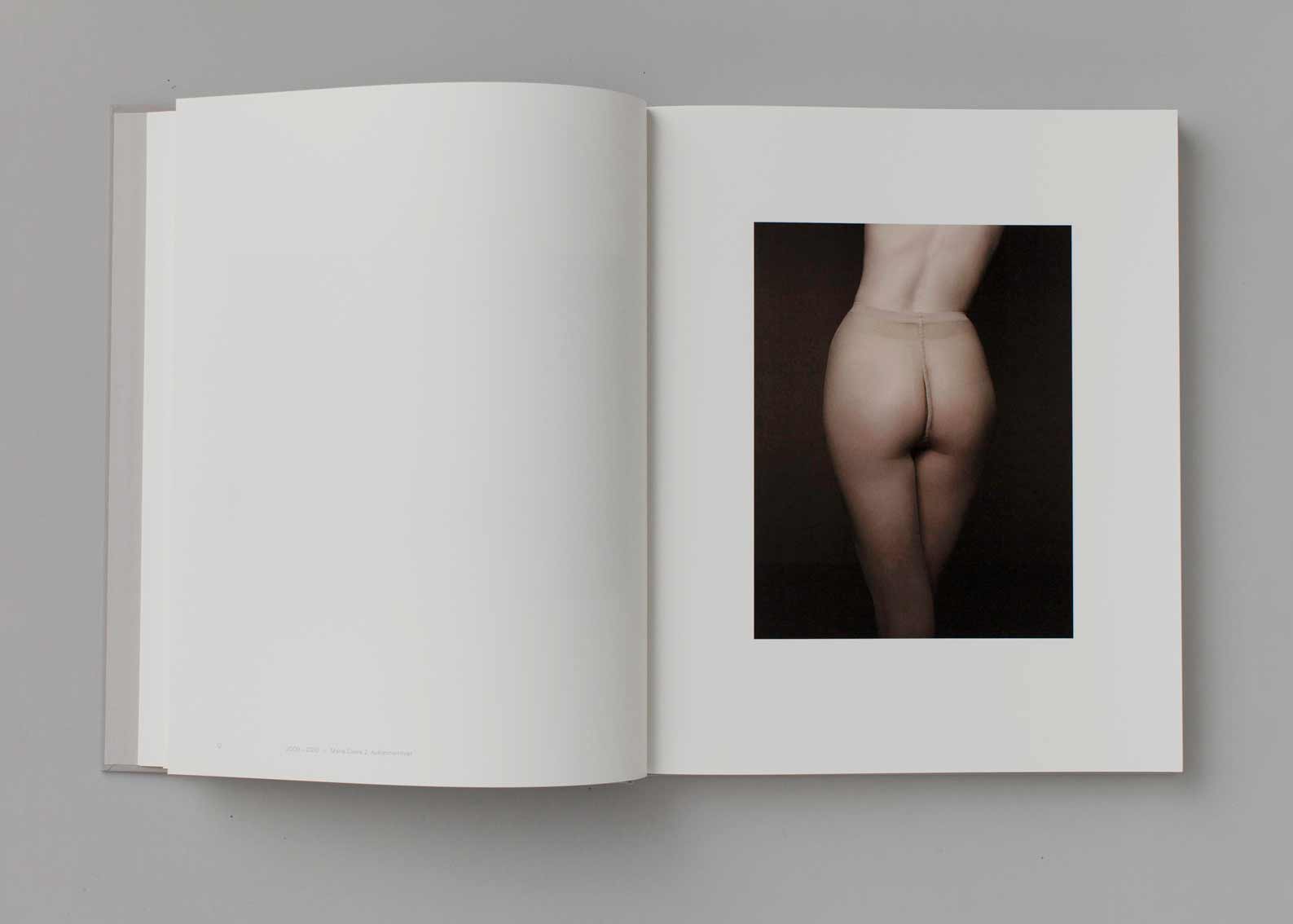

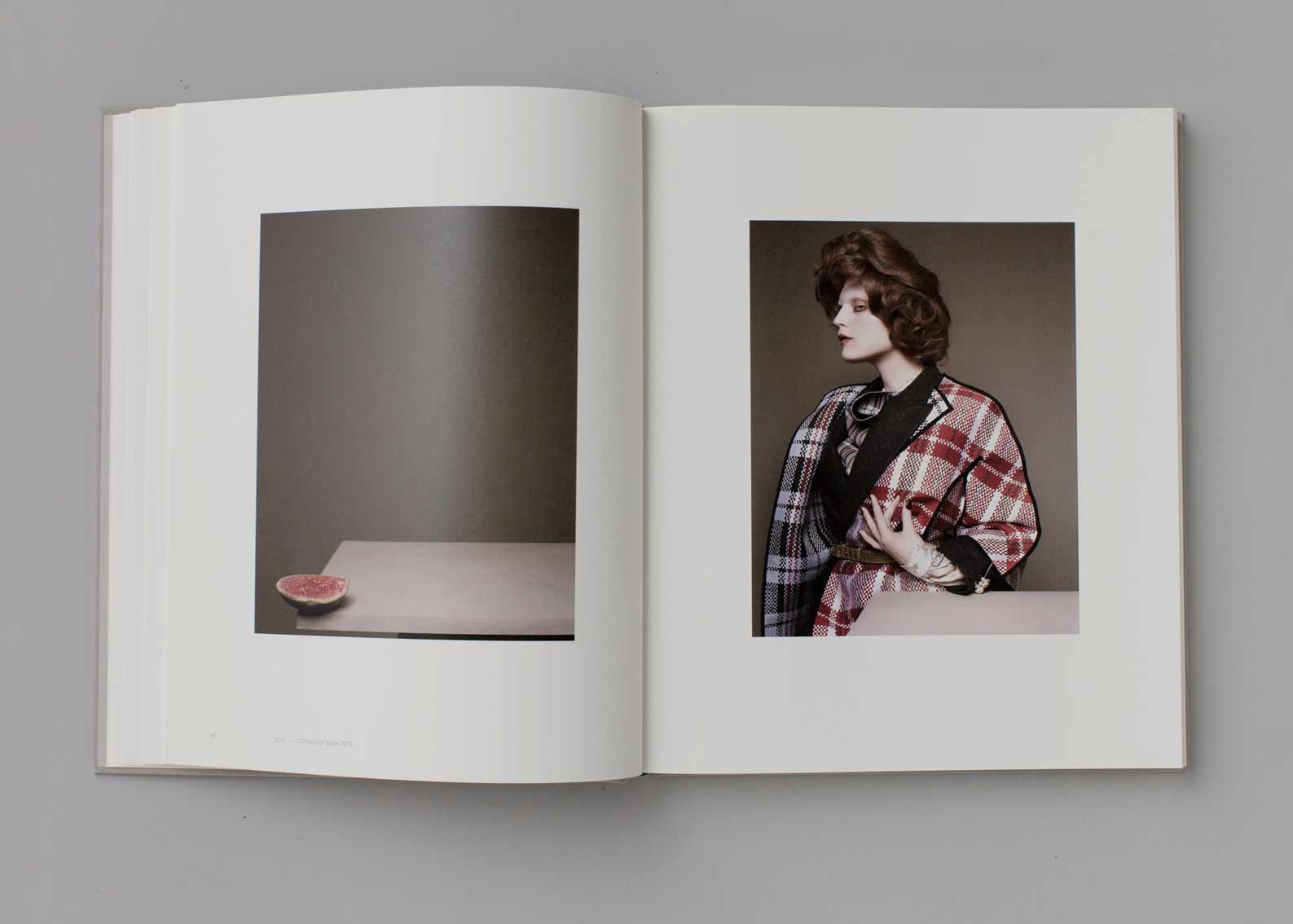

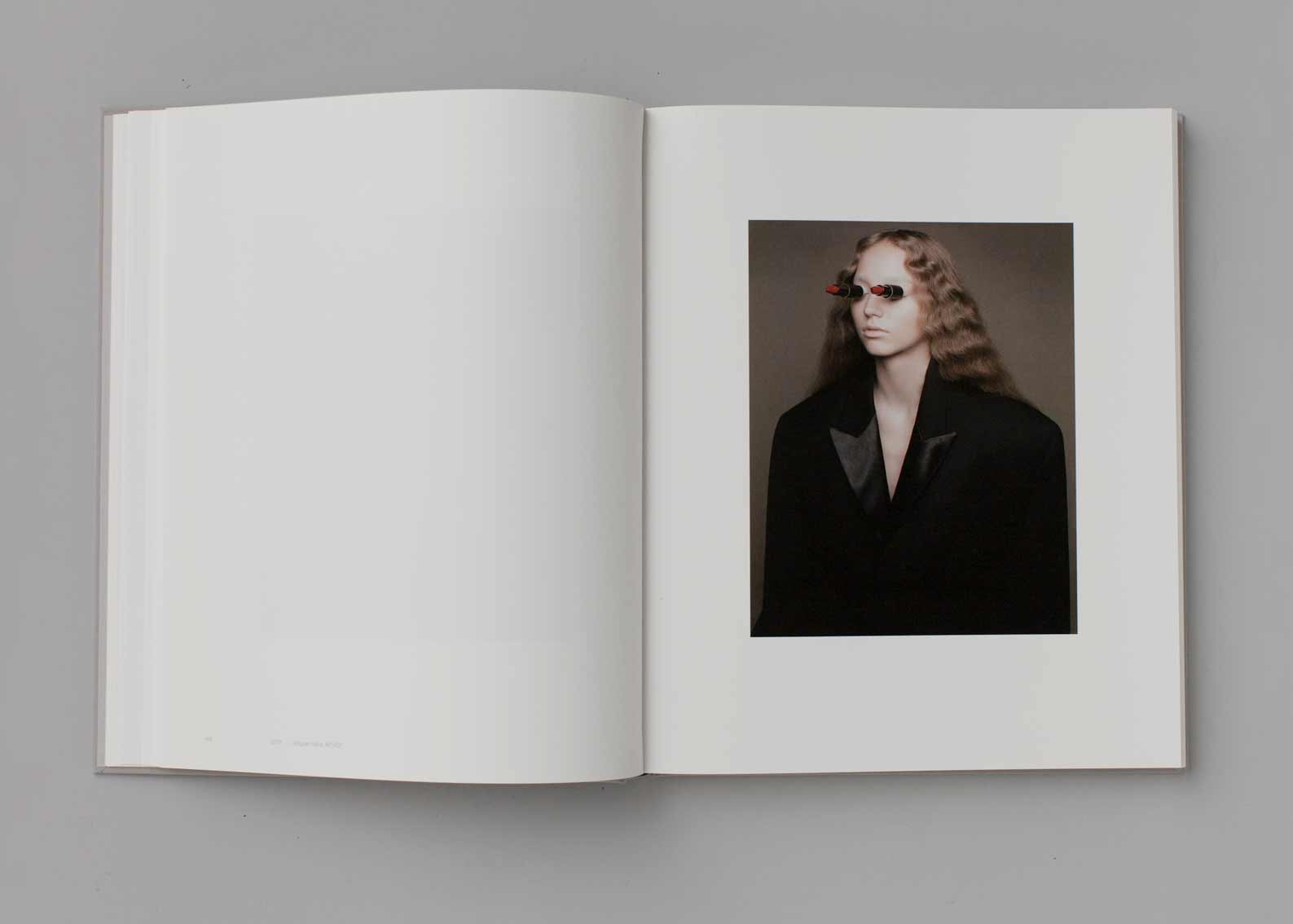

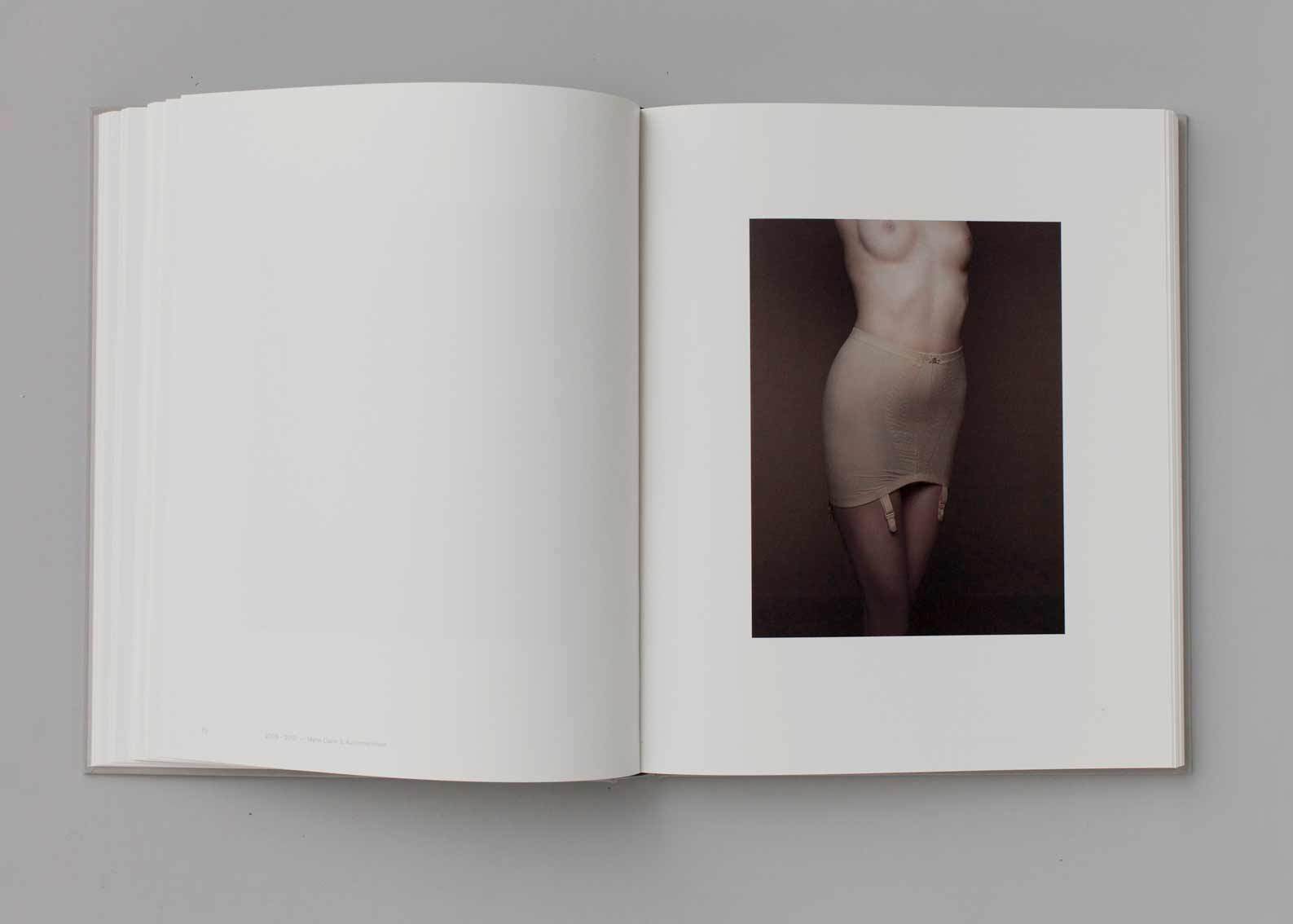

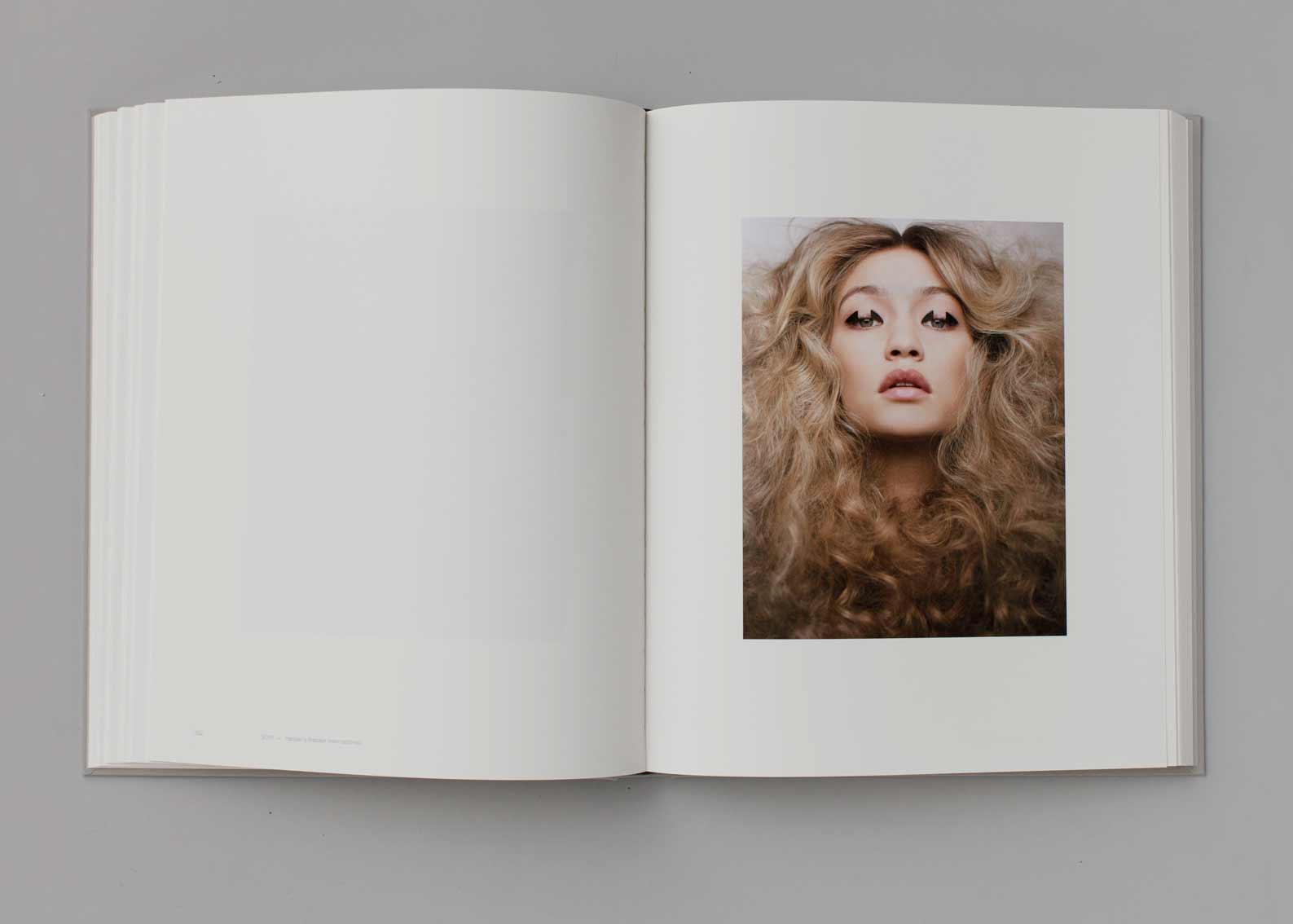

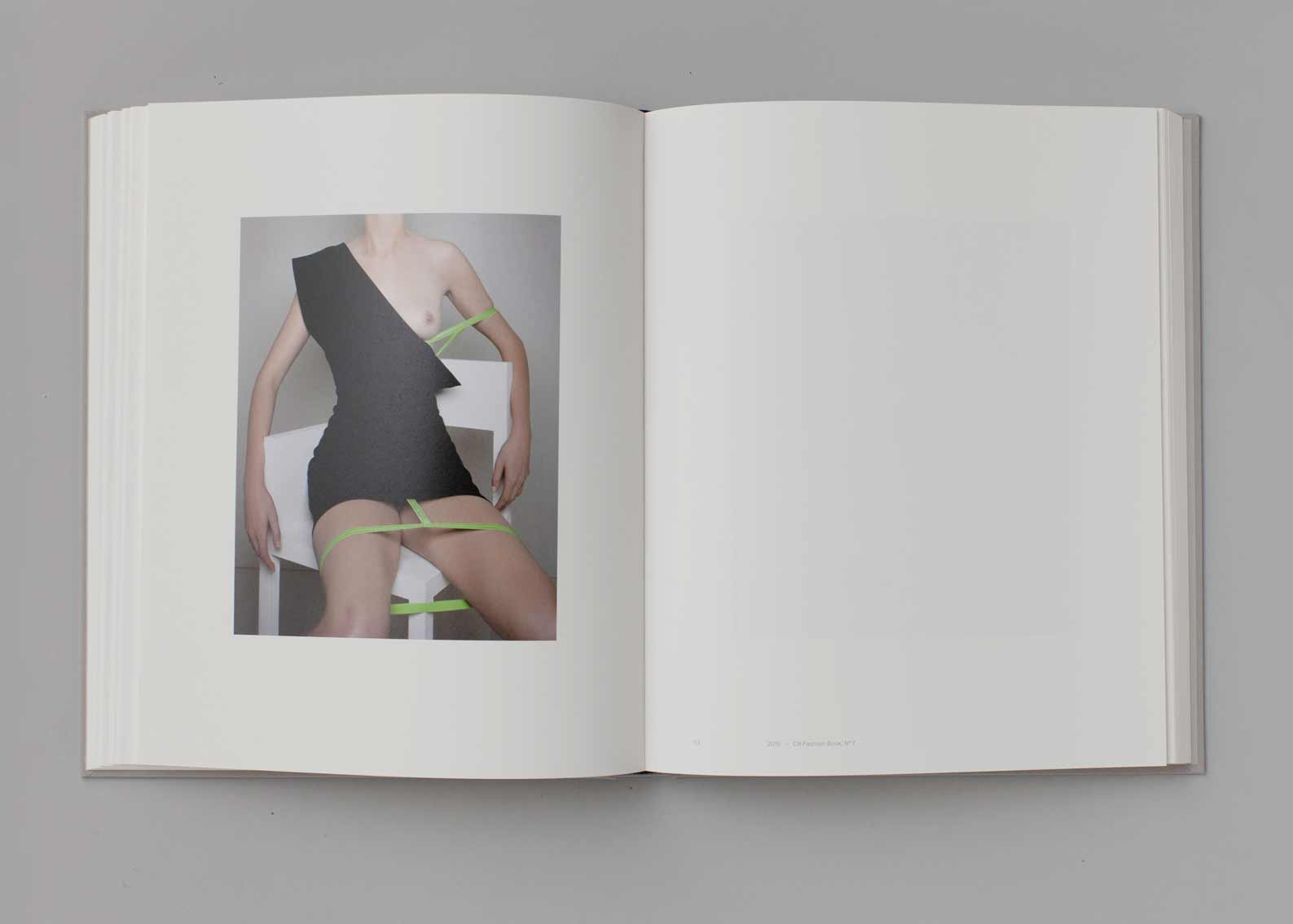

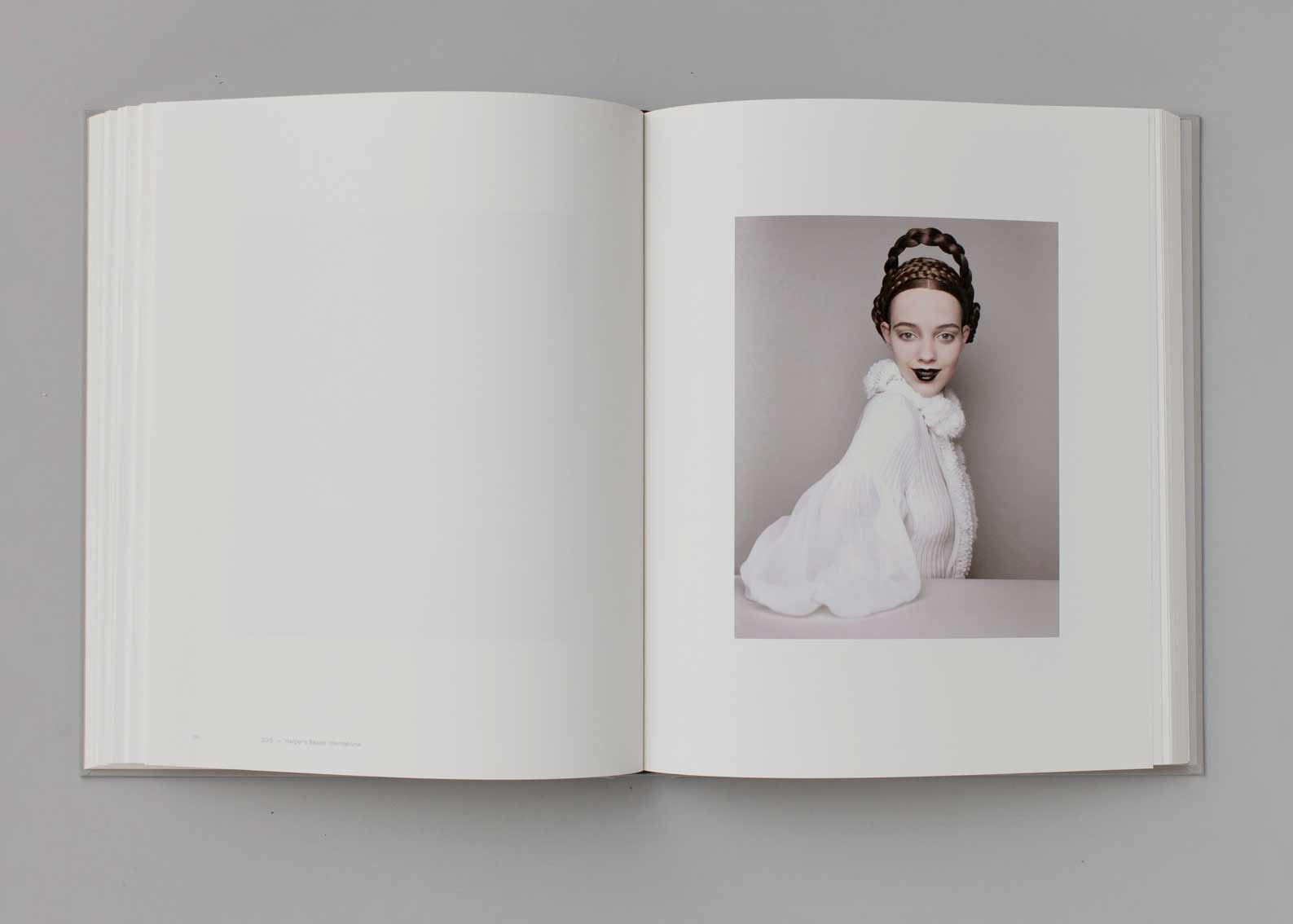

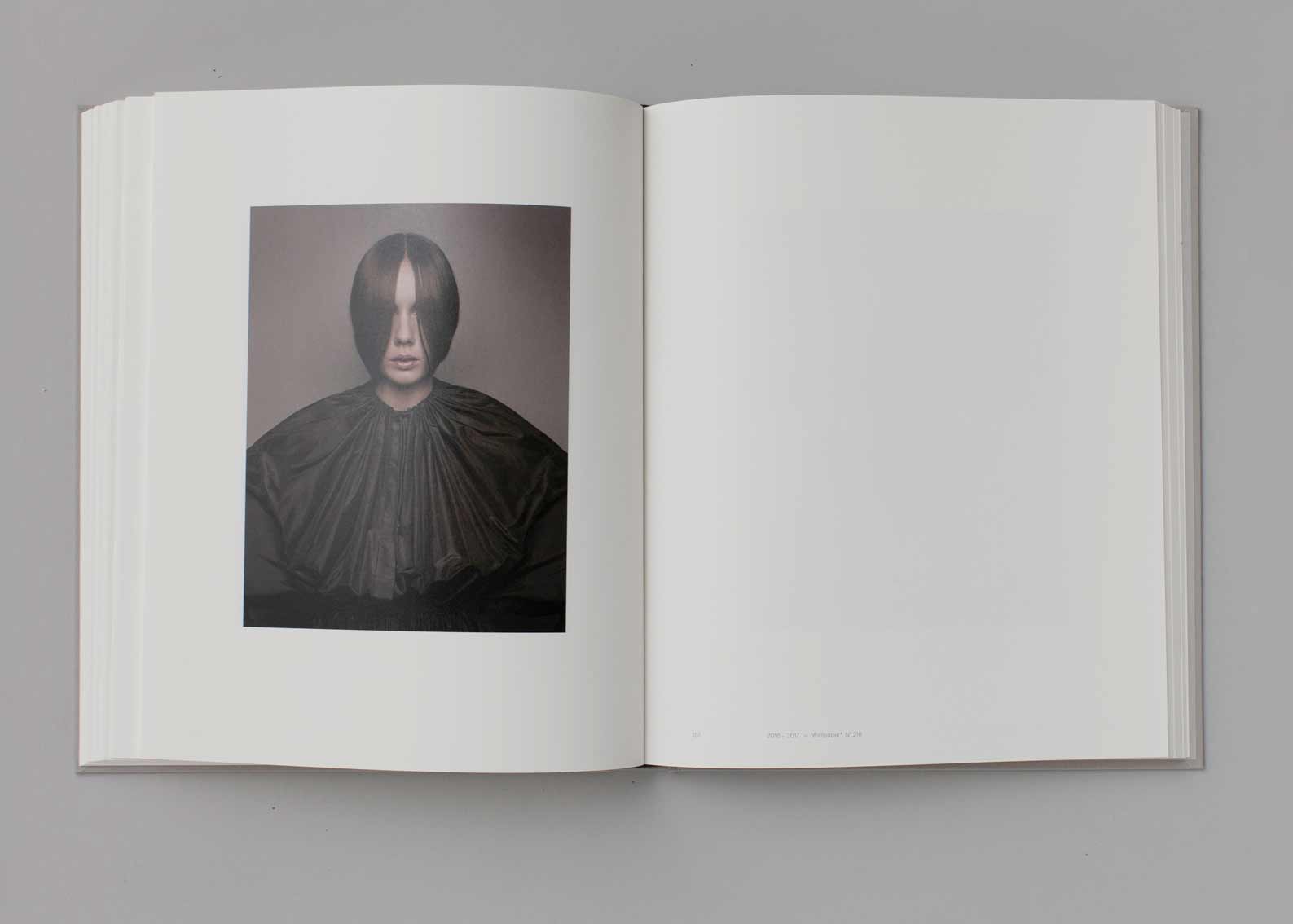

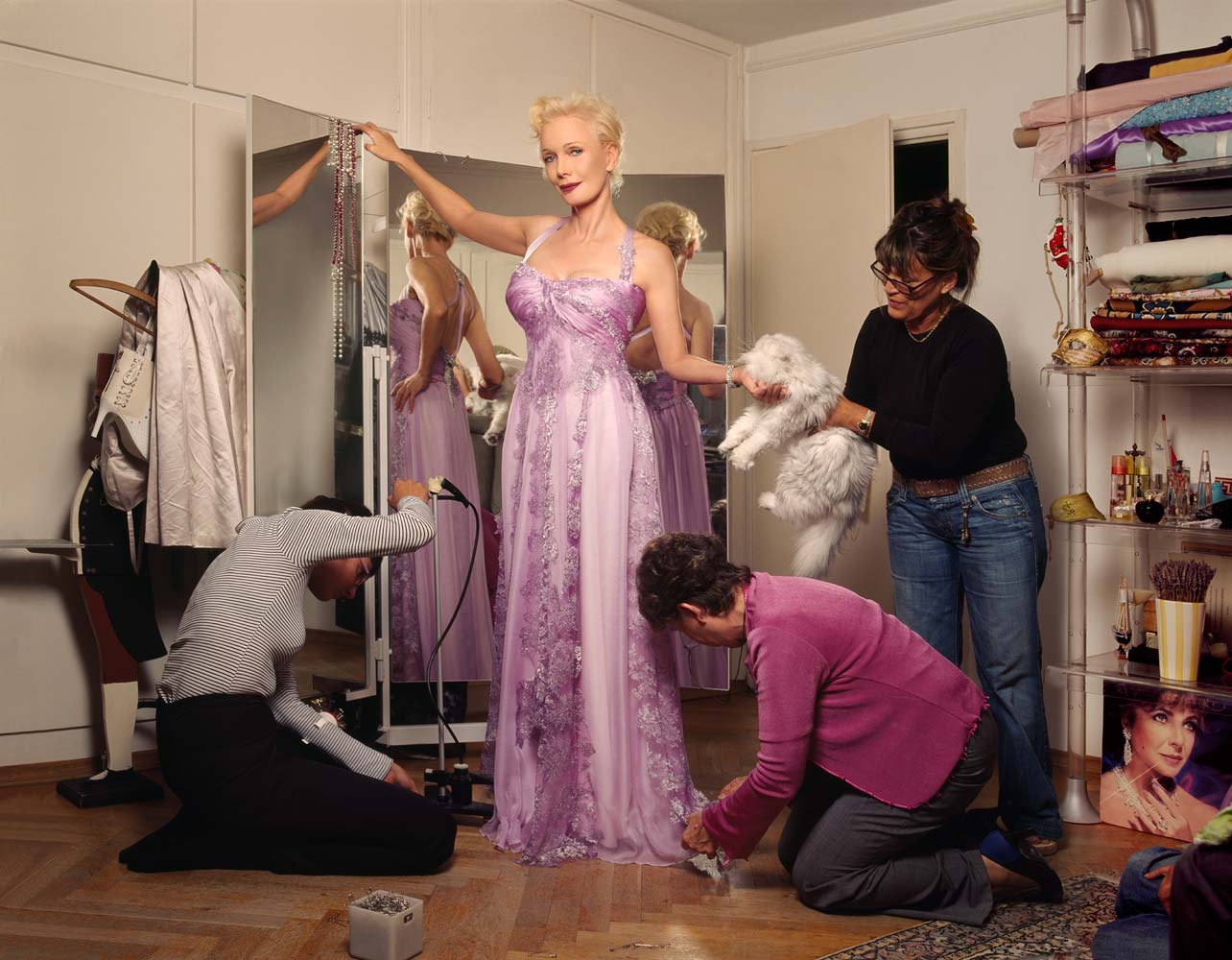

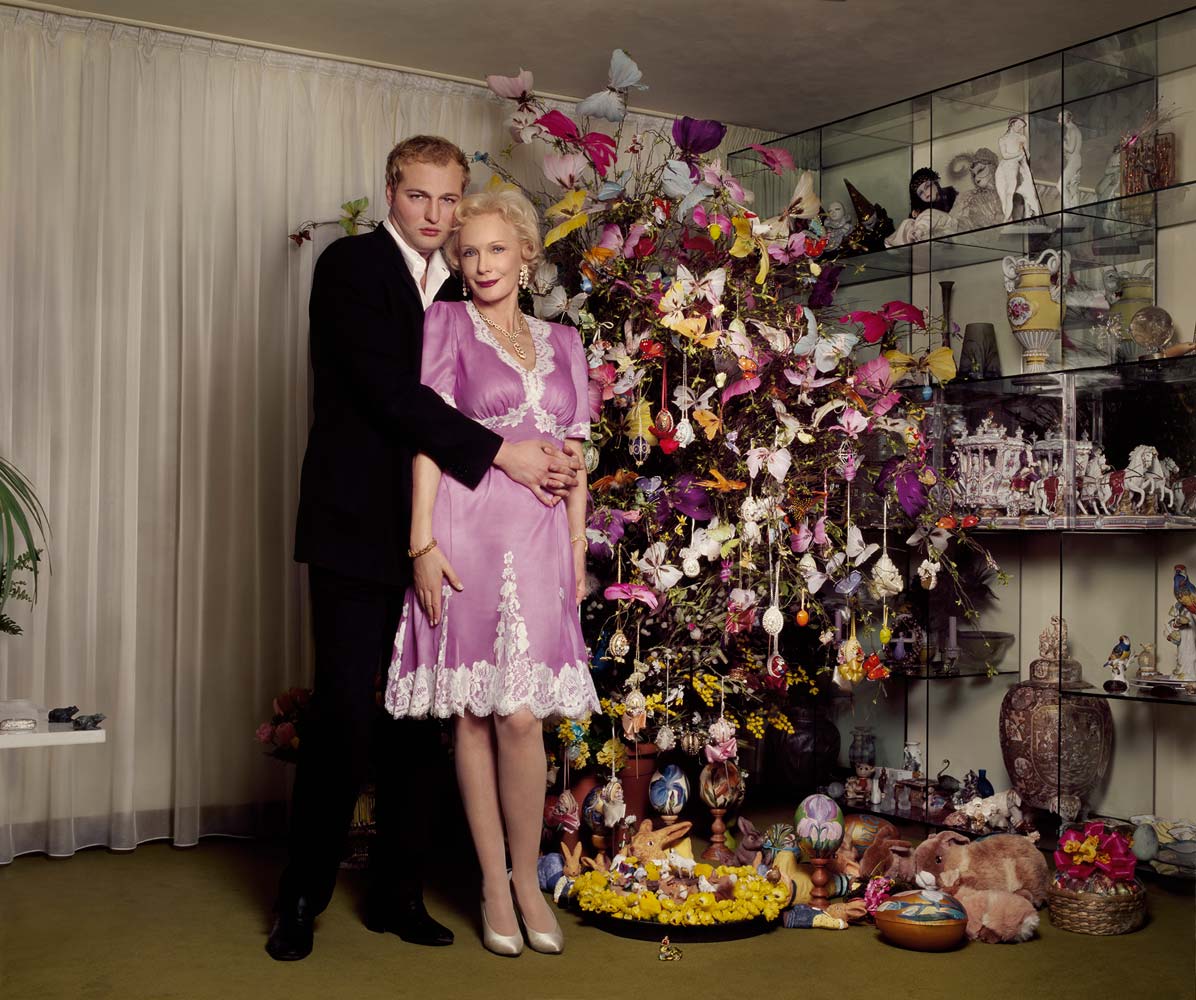

Brigitte Niedermair’s images are always striking for their extreme accuracy and incisiveness: nothing is left to chance in her works, which

are always painstakingly planned yet so very “real”. But the aim of the Meranese artist is not to engage in “realistic” photography, but to

guarantee the authenticity of the vision, adopting a highly painterly approach and attributing great importance to so-called postproduction.

She favours female subjects: she prefers to portray women and manages to lend them a dignity and aura that make her

images much closer to a “photographic painting” than a documentary shot.

Indeed the series of photographs of women that Brigitte Niedermair has produced in recent years might first seem an attempt to archive

and record various situations in the female world. This could be partially true, given the artist’s keen interest in the sociological and

anthropological aspects of the subjects she photographs, but unlike the levelling of the individual identity which occurs in documentary

photography Brigitte Niedermair is keenly interested in bringing to light the individual, singular characteristics of her subjects.

Although the spectator perceives the forceful genuinity of the subject of the photograph, what also comes across is the great allure of the

reproduced image, which is devoid of spontaneity and highly staged. This by no means signifies that Brigitte Niedermair’s photographs

exalt make-believe and pretence, quite the opposite: her recovery of the paint-erly tradition of the portrait attempts to re-establish a critical

relationship with reality. Her calculated handling of the image brings to light the single individuals, or rather the single women, with highly

relationship with reality. Her calculated handling of the image brings to light the single individuals, or rather the single women, with highly

distinct connotations. The subject, or rather the subjects represented are called into question, and the emphasis placed on the staging

and the deployment of compositional strategies suggest a keen pursuit of authenticity.

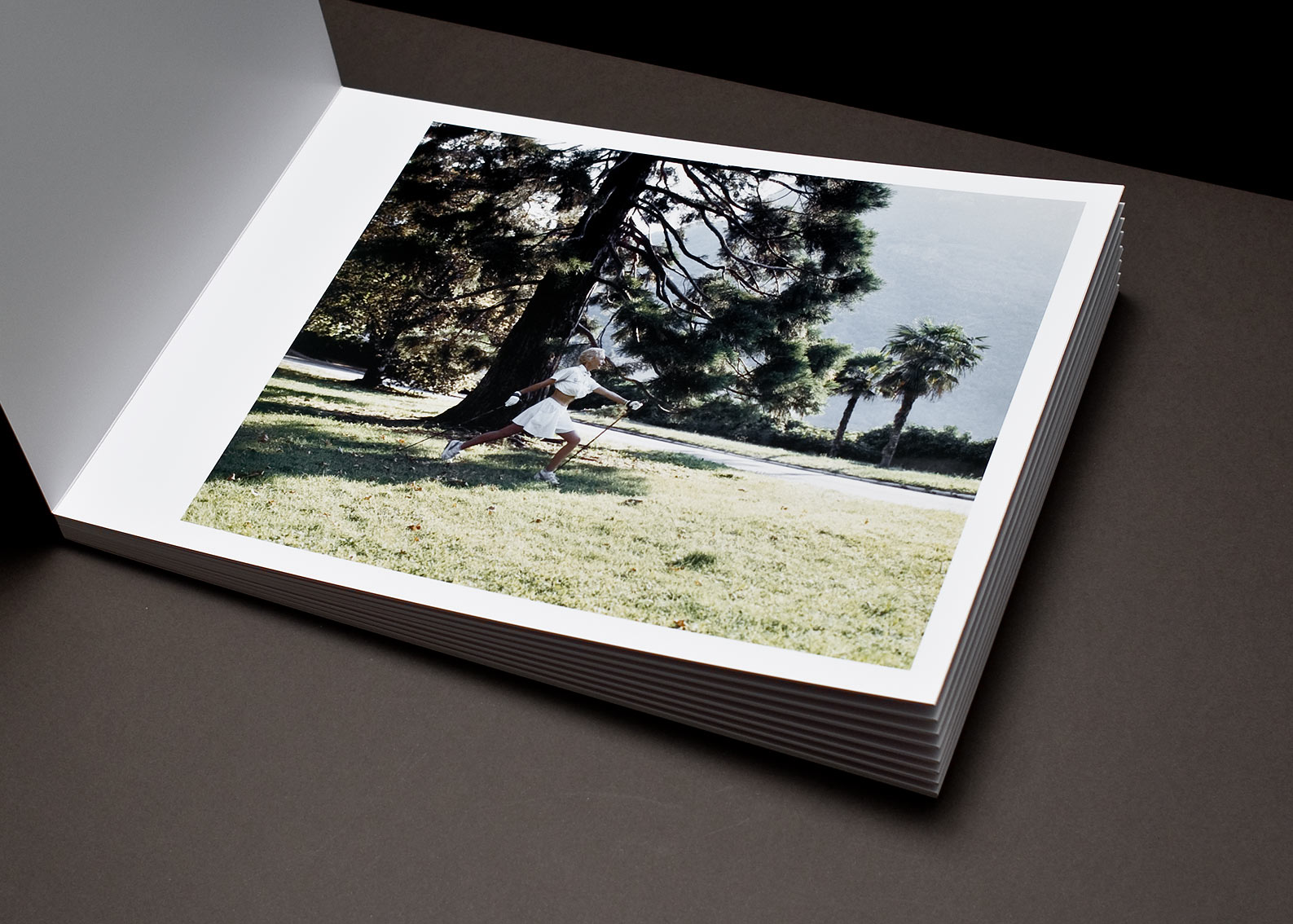

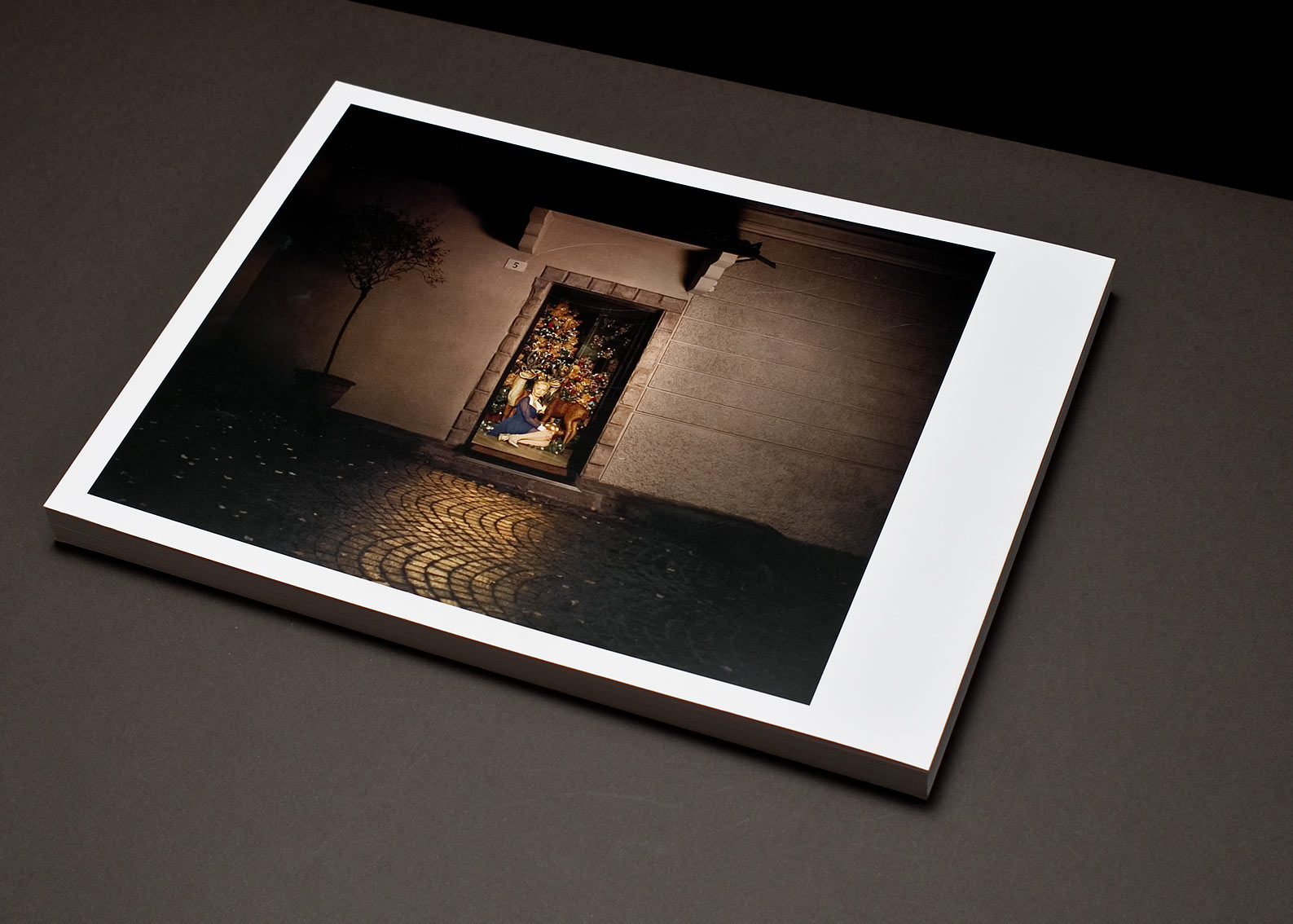

In Madame Hirsch, for the first time Brigitte Niedermair has taken on a sort of diary in images of various episodes in the life of Renate

Hirsch Giacomuzzi, simply following the natural “lifestyle” moments that are part of her subject’s daily routine and the habitual

appointments that make up Madame’s cosmopolitan existence. From the de rigueur skiing holiday in St. Moritz, to the summer break in

Cala di Volpe in Sardinia, the traditions that surround Christmas and Easter and the unmissable annual debutantes’ ball at the Vienna

Opera House, the spectator is plunged into a series of “natural” film sets captured by the camera. It appears to follow the tradition of a

kind of documentary “log book” capturing a year-long journey, but the technique is anything but that of a documentary, coming much

closer to hyper-realism. Indeed the backgrounds look like a series of sets, generating images that merit the description of “painted

theatre”. The photographs of Madame

BRIGITTE NIEDERMAIR

Brigitte Niedermair (Merano, 1971) has made photographs for over twenty years, spanning independent artistic enquiry and fashion image-making. Since the 1990s, her projects have centered on the meaning of identity, the affect of representing the female body, and the agency of viewership. More broadly, Niedermair’s approach to photography has been a constant exploration of time and memory that reflects onto the languages of the history of art.

Her work has been shown internationally, with monographic exhibitions including Somewhere, Stadtgalerien Schwaz (2007); Madame Hirsch, Museion, Bolzano (2009); Holy Cow, Foto-Forum, Bolzano (2009); Sister, Galleria Galica, Milan (2009); Let’s Get Married, A38 Cultural Center, Budapest (2011); Horizon, Transition_Giorgio Morandi ⁄ Are you still there, MAMbo – Museo Morandi, Bologna (2015); Screenshot (with Martino Gamper), One Poultry ⁄ Wallpaper*, London (2017); Transition, Palazzo Borromeo, Milan (2017), Eccehomo, Castel Tirolo, (2018).

Her fashion images have been featured in international publications including CR Fashion Book by Carine Roitfeld, Harper’s Bazaar, Wallpaper*, Dior Magazine, W, Citizen K, and Vogue Italia.

Her works are included in private collections, museums and public institutions in Italy and abroad. She lives in Merano and works in Paris, Milan, London and New York.

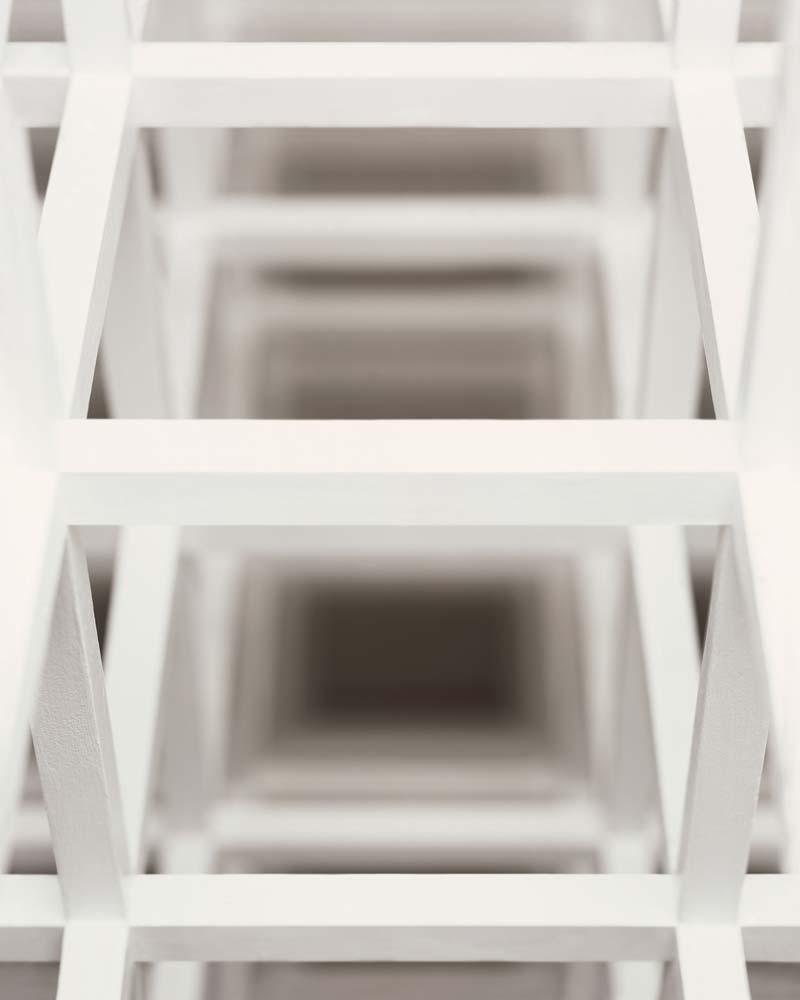

SOL LEWITT

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Inverted Spiraling Tower, 1988)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Corner Piece 1 2 3 4 5 6, 1979)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #1267: Scribbles, 2010)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #263: A wall divided into 16 equal

parts with all one-, two-, three-, four- part combinations

of lines in four directions, 1975)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Inverted Spiraling Tower, 1987)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Complex Form #34, 1990)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Structure Black, 1962)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #123A: The first drafter draws a not straight vertical line as long as possible. The second drafter draws a line next to the first one, trying to copy it. The third drafter does the same, as do as many drafters as possible. Then the first drafter, followed by the others, copies the last line drawn until both ends of the wall are reached, 1991)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Inverted Spirlanig Tower, 1987)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Geometric Figure #10 ( ⁄ ), 1977)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Complex Form #34, 1990)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

Trittico ⁄ Triptych (1/3)

(Wall Drawing #1267: Scribbles, 2010)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Trittico ⁄ Triptych (2/3)

Trittico ⁄ Triptych (3/3)

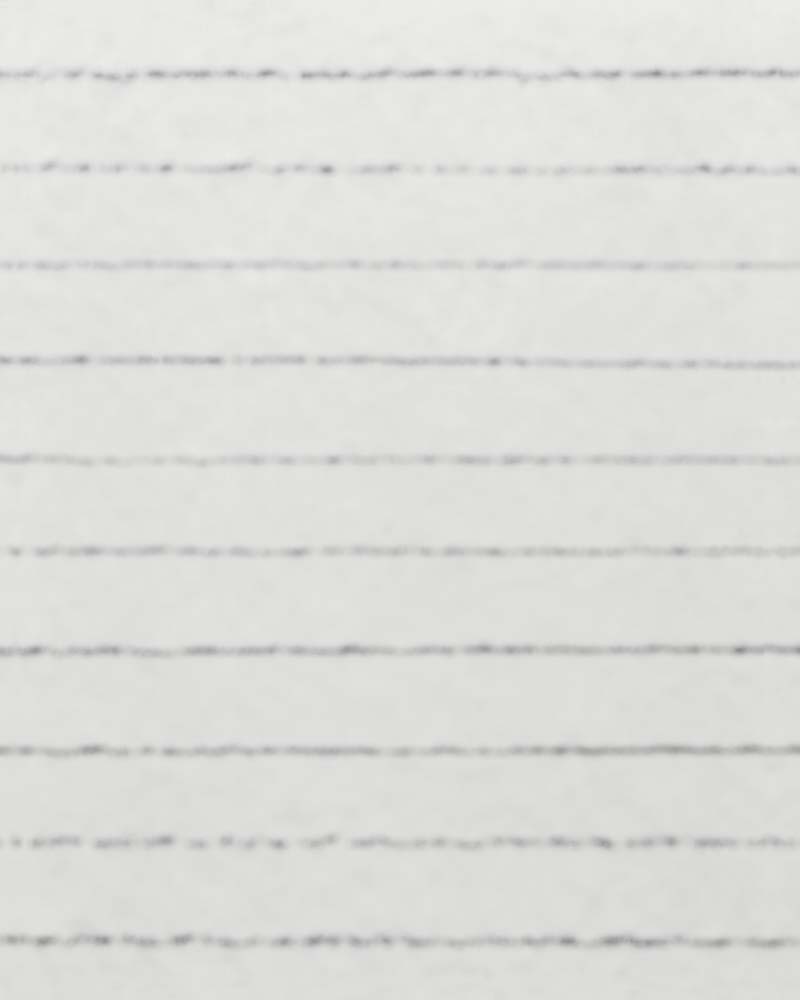

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #150: Ten thousand one-inch (2.5cm) lines evenly spaced on each of six walls, 1972)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Structure Black, 1962)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Complex Form #34, 1990)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #263: A wall divided into 16 equal parts with all one-, two-, three-, four- part combinations of lines in four directions, 1975)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #1267: Scribbles, 2010)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Structure Black, 1962)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #150: Ten thousand one-inch (2.5cm) lines evenly spaced on each of six walls, 1972)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #1267: Scribbles, 2010)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #51: All architectural points connected by straight lines, 1970)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

Dittico ⁄ Diptych

Sinistra ⁄ Left (Untitled (B3 Model), 1966)

Destra ⁄ Right (Early Wood Structure, 1962 ca.)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Corner Piece 1 2 3 4 5 6, 1979)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Structure with Standing Figure, 1963)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #263: A wall divided into 16 equal parts with all one-, two-, three-, four- part combinations of lines in four directions, 1975)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #1104: All combinations of lines in four directions. Lines do not have to be drawn straight (with a ruler), 2004)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

Sol LeWitt under the lenses

(Wall Drawing #1104: All combinations of lines in four directions. Lines do not have to be drawn straight (with a ruler), 2004)

2018

Stampa fotografica ⁄ Photographic print

69 x 55 in ⁄ 175 x 140 cm

SCREENSHOT

Screenshot

2016

Mona Lisa

Leonardo da Vinci

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

The young hare

Albrecht Dürer

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Girl with the pearl

Johannes Vermeer

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Les demoiselles d'Avignon

Pablo Picasso

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Paysage à l’Estaque

George Braque

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Tableau 1

Piet Mondrian

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

The black square

Kazimir Malevich

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Flora on sand

Paul Klee

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Monochrome

Piero Manzoni

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Blueprints

Robert Rauschenberg

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Study for homage to the square

Josef Albers

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Concentric squares

Frank Stella

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Wall structure Blue

Sol LeWitt

c-print

140x170 cm

Screenshot

2016

Squares

Sol LeWitt

c-print

140x170 cm

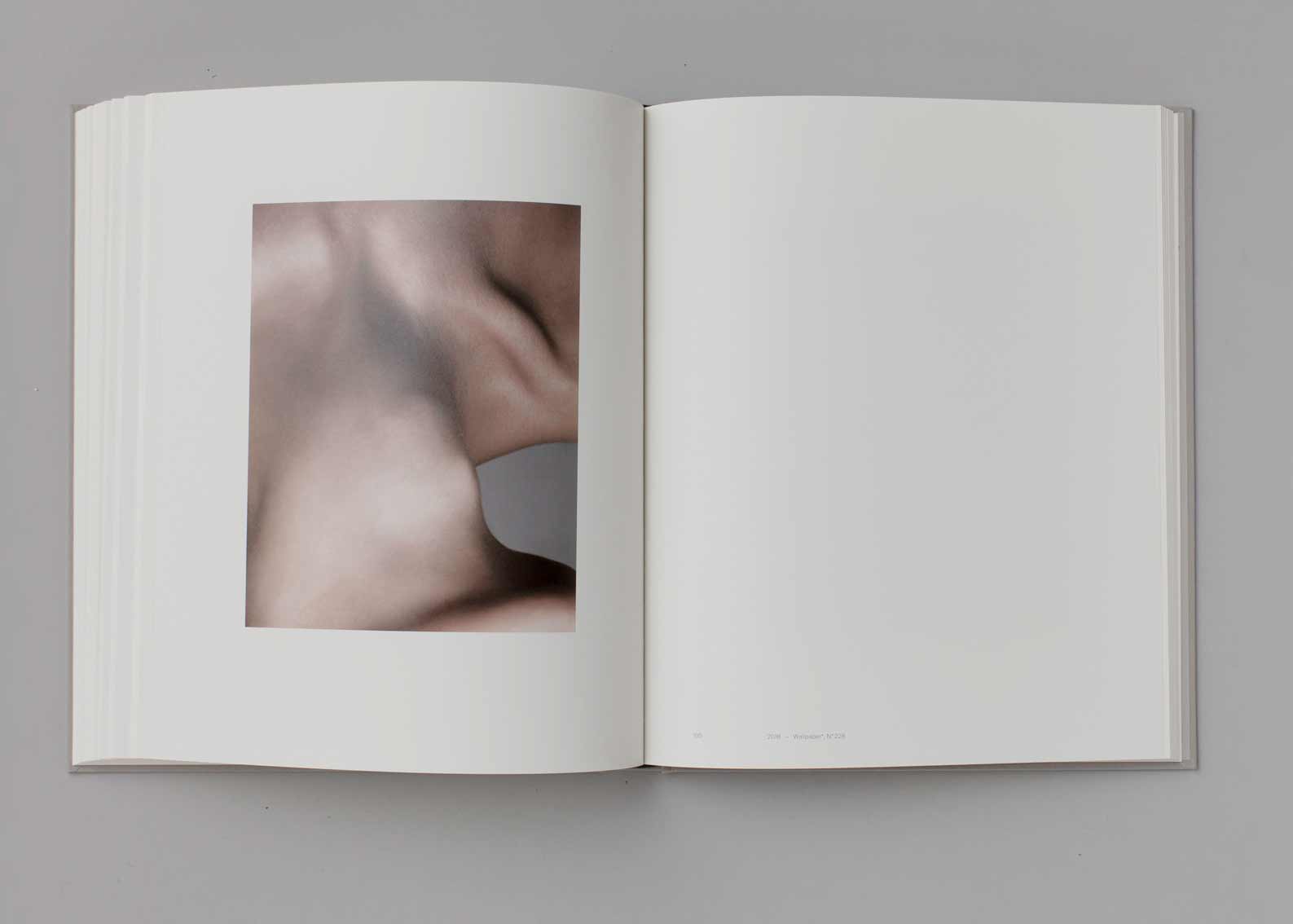

ECCEHOMO

eccehomo

2009

Füße ⁄ Piedi

c-print

175,3 x 140 cm

eccehomo

2009

Arm ⁄ Braccio

c-print

140 x 175,4 cm

eccehomo

2009

Körper ⁄ Corpo

c-print

c-print, 140 x 167 cm

eccehomo

2009

Bauch ⁄ Addome

c-print

175,9 x 140 cm

ARE YOU STILL THERE

“are you still there”

2011-2014

“Akehat Khufu/Great Pyramid”

Pharaoh Khufu/Thoth_Giza/Egypt

c-print

13 X 18 cm

119 X 149

selected works 5 of 16 works

“are you still there”

2011-2014

“The shining Pyramid”

Pharaoh Sneferu_Red Pyramid-Dahshur/Egypt

c-print

13 X 18 cm

119 X 149

selected works 5 of 16 works

“are you still there”

2011-2014

“The southern shining Pyramid”

Phararo Sneferu_Bent Pyramid_Dahshur/Egypt

c-print

13 X 18 cm

119 X 149

selected works 5 of 16 works

“are you still there”

2011-2014

“Sneferu endures”

Phararo Sneferu(?)_Meidum/Egypt

c-print

13 X 18 cm

selected works 5 of 16 works

“are you still there”

2011-2014

“Great is Khafre”

Pharaoh Khafre_Giza/Egypt

c-print

13 X 18 cm

selected works 5 of 16 works

TRANSITION_GIORGIO MORANDI

transition_Giorgio Morandi

2012-2013

transition I

c-print

57 X 73,3 cm

selected works 7 of 24 works

transition_Giorgio Morandi

2012-2013

transition II

c-print

57 X 73,3 cm

selected works 7 of 24 works

transition_Giorgio Morandi

2012-2013

transition III

c-print

57 X 73,3 cm

selected works 7 of 24 works

transition_Giorgio Morandi

2012-2013

transition IV

c-print

57 X 73,3 cm

selected works 7 of 24 works

transition_Giorgio Morandi

2012-2013

transition V

c-print

57 X 73,3 cm

selected works 7 of 24 works

transition_Giorgio Morandi

2012-2013

transition VI

c-print

57 X 73,3 cm

selected works 7 of 24 works

transition_Giorgio Morandi

2012-2013

transition VII

c-print

57 X 73,3 cm

selected works 7 of 24 works

DUST

Dust

2007

dust I

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

157x125 cm

Dust

2007

dust II

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

Dust

2007

dust III

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

Dust

2007

dust IV

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

Dust

2007

dust V

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

157x125 cm

Dust

2007

dust VI

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

Dust

2007

dust VII

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

Dust

2007

dust VIII

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

Dust

2007

dust IX

c-print

0,33 x 0,26 cm in series

157x125 cm

THE PRESENT

The Present

2012

the present I

c-print

26,0 x 33,0 cm in series

The Present

2012

the present II

c-print

26,0 x 33,0 cm in series

The Present

2012

the present III

c-print

26,0 x 33,0 cm in series

The Present

2012

the present IV

c-print

26,0 x 33,0 cm in series

The Present

2012

the present V

c-print

26,0 x 33,0 cm in series

The Present

2012

the present VI

c-print

26,0 x 33,0 cm in series

The Present

2012

the present VII

c-print

26,0 x 33,0 cm in series

EDEN

Eden

2012

c-print

145x173 cm

MADAME HIRSCH

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

16:20 April /

Bozen / Osterbaum

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

18:20 Mai /

Venedig / Fenice-Zauberflote

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

06:45 Juli /

Talferpromenade / Bozen / Taegliches Fitness

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

17:00 September /

Bozen / Privatdomizil / Tee von Amerik serviert

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

15:30 Juli /

Jenesien / Auf der Schaukel

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

17:45 Oktober /

Muenchen / Oktoberfest

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

14:10 September /

Muenchen / Anprobe in der Hout Couture Atelier

1 c-print

152x180

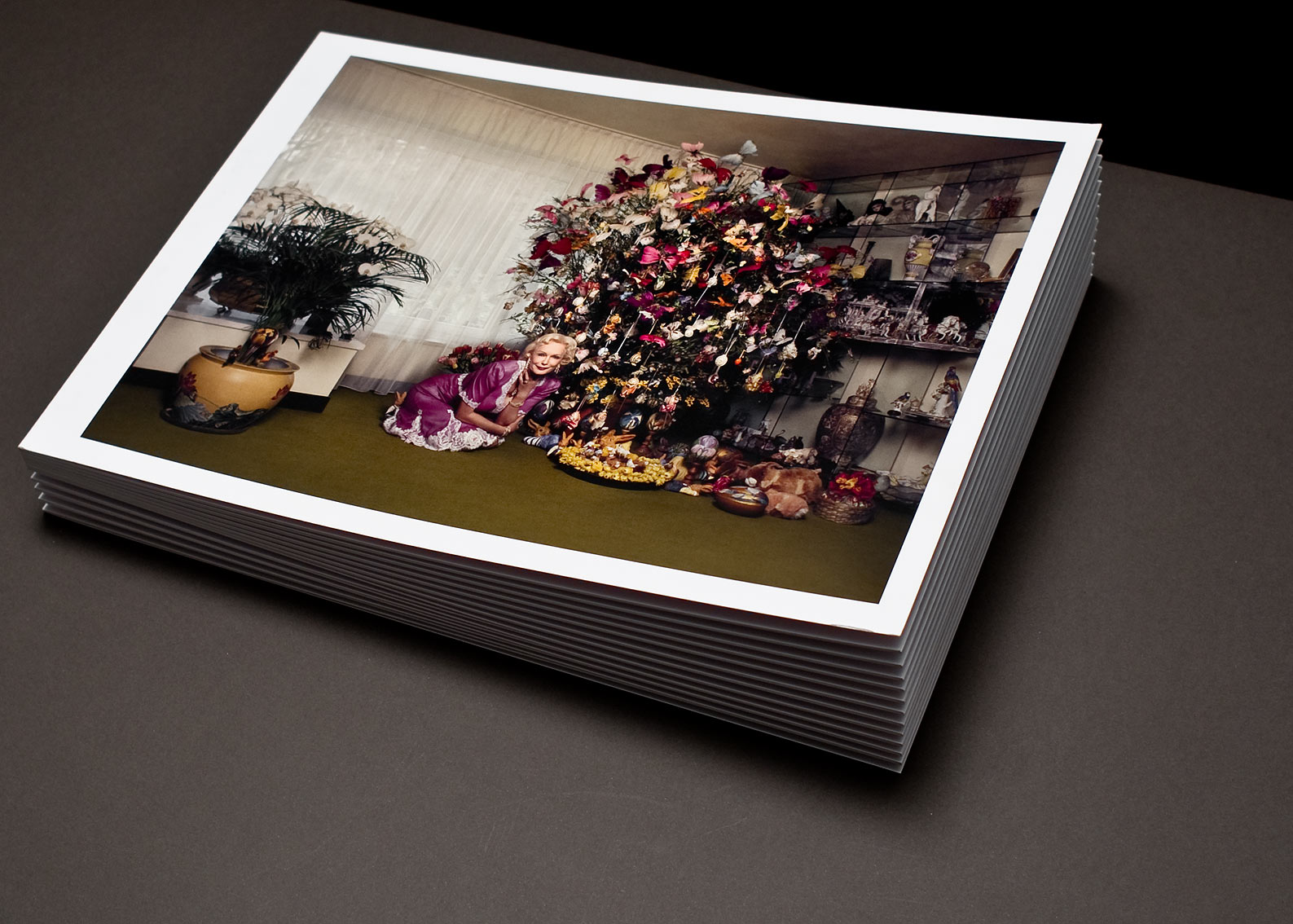

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

19:00 Dezember /

Bozen / Privatdomizil / 1.Advent

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

20:00 Dezember /

Bozen / Weihnachtsfest

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

18:30 Dezember /

Bozen / Nikolausfeier

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

12:05 Januar /

Hotel Palace / St.Moritz / Ankunft

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

12:00 Januar /

St.Moritz / Polo / Fototermin

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

19:00 Wien /

Opernball / In der Imperial Suite

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

20:15 Februar /

Hotel Imperial / Wien / Vor dem Sissiportrait

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

16:20 August /

Ritten-Jenesien / Am See

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

15:10 Marz /

Bozen / Privatdomizil Osterbaum

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

18:00 April /

Ostern1 / Privatdomizil / Mutter und Sohn Leander

1/3

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

18:00 April /

Ostern1 / Privatdomizil / Mutter und Sohn Leander

2/3

1 c-print

152x180

Madame Hirsch

2006-2007

18:00 April /

Ostern1 / Privatdomizil / Mutter und Sohn Leander

3/3

1 c-print

152x180

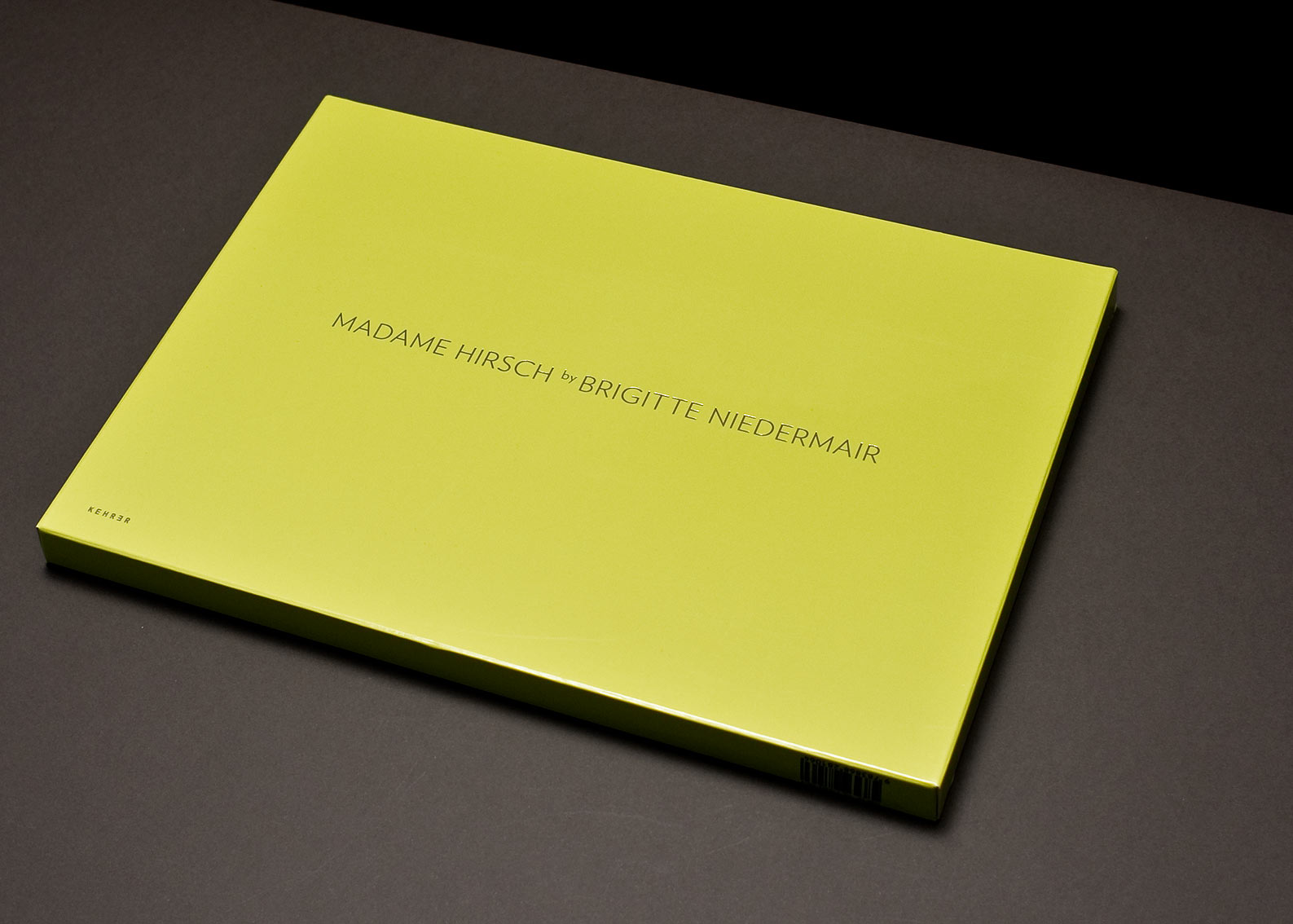

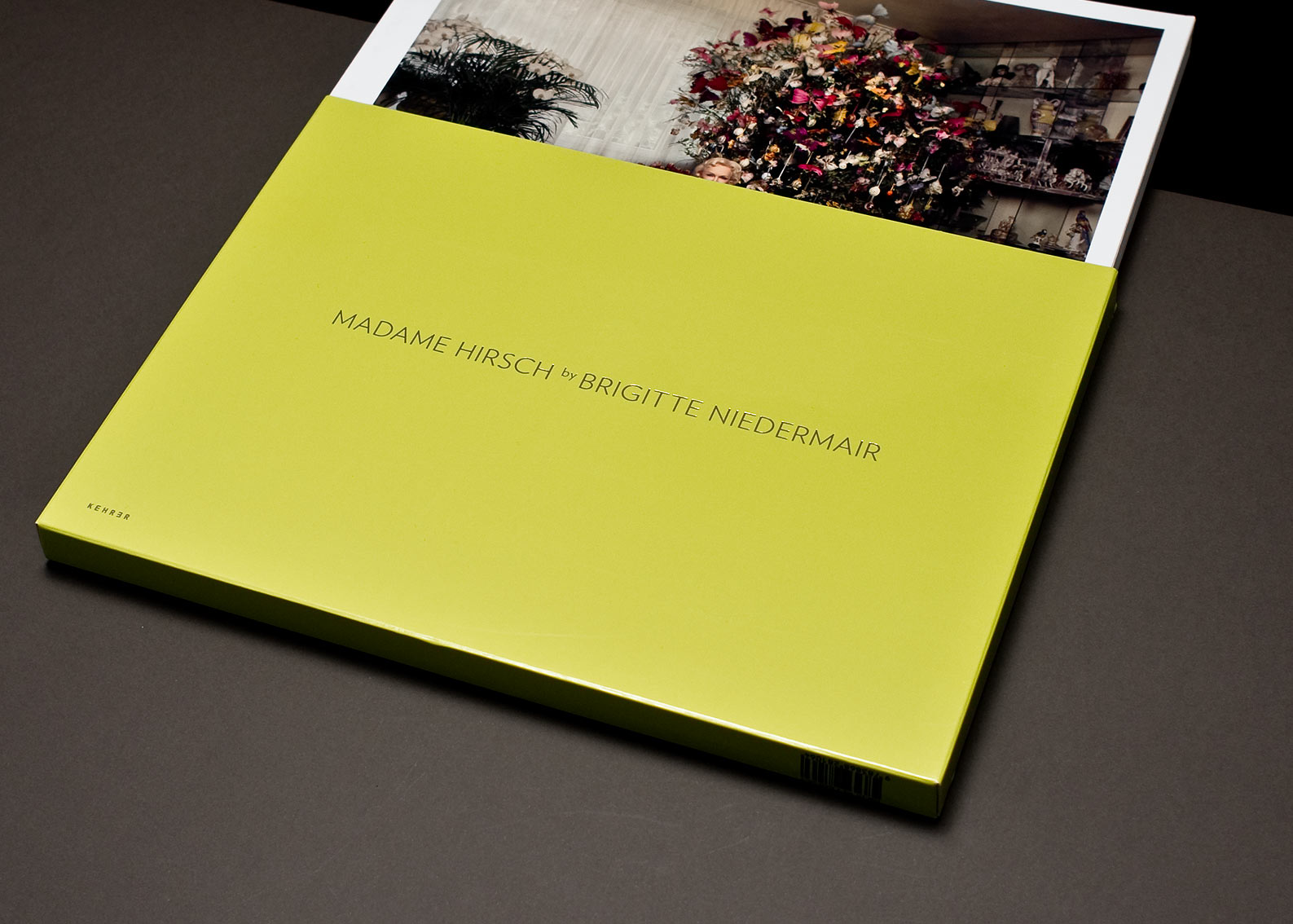

MADAME HIRSCH BOOK

MADAME HIRSCH

2009

Accordion-folded book w. slipcase

in a slipcase, without text

27 color illustrations

Kehrer

38 x 28 cm

ISBN 978-3-86828-106-4

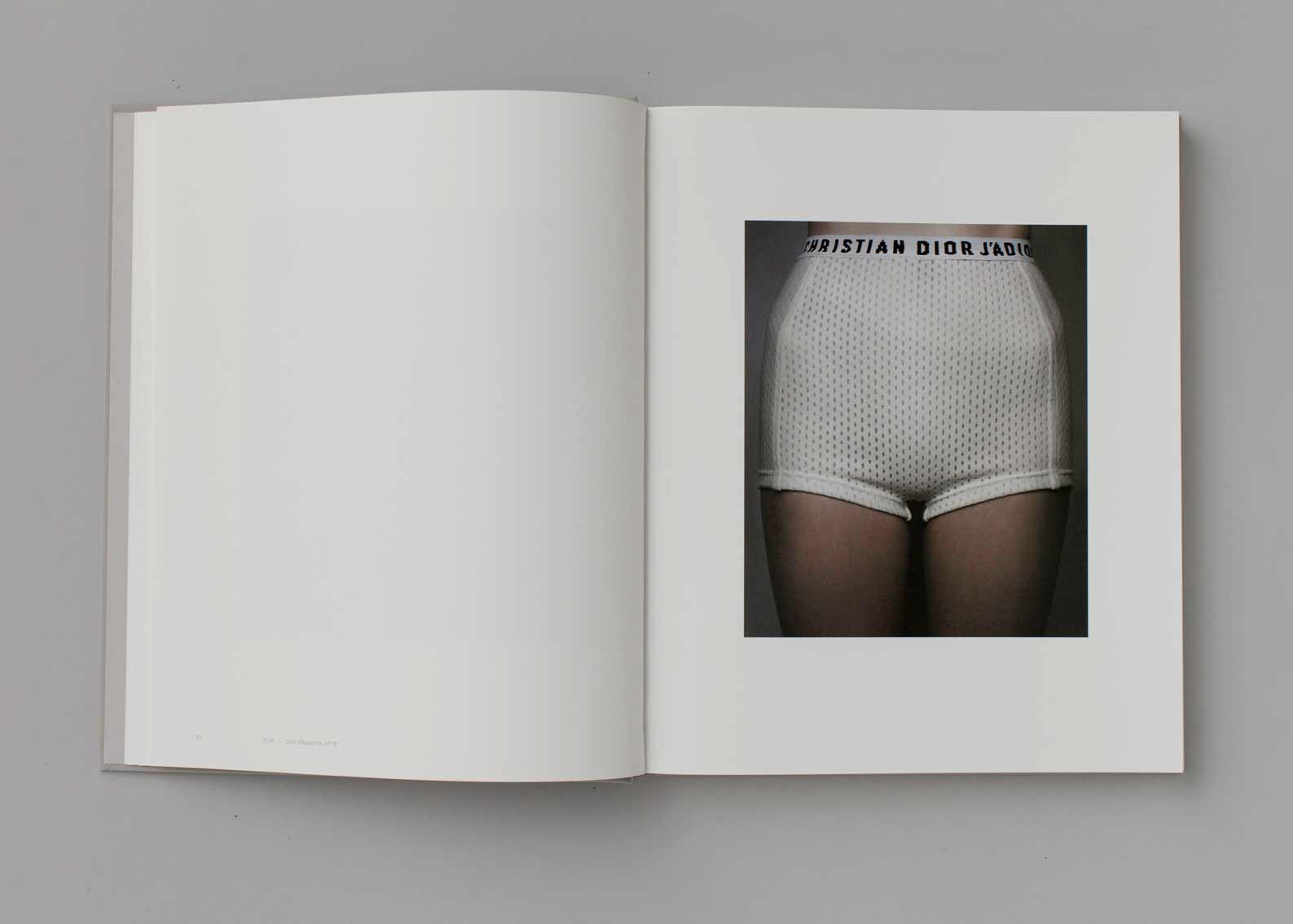

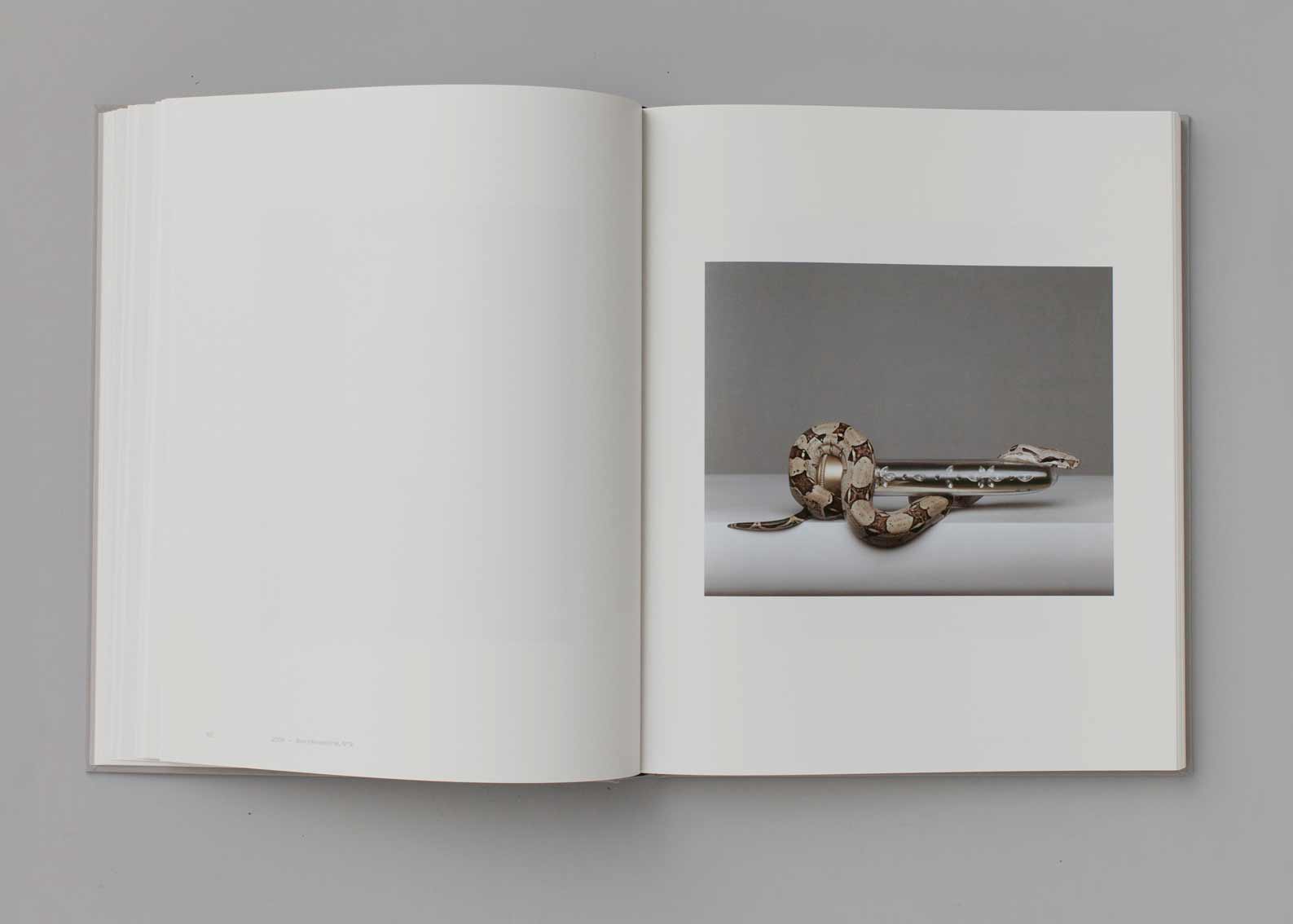

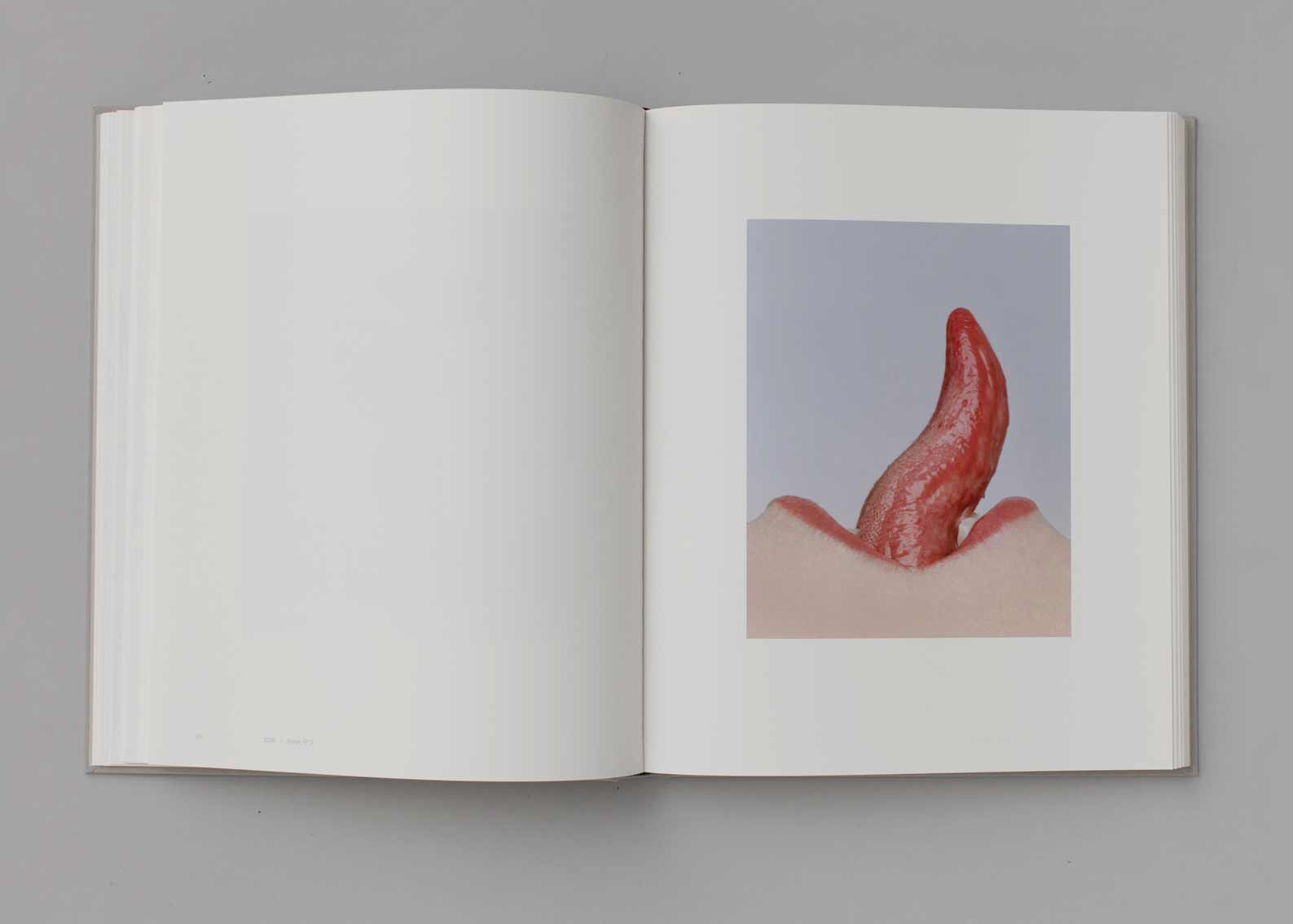

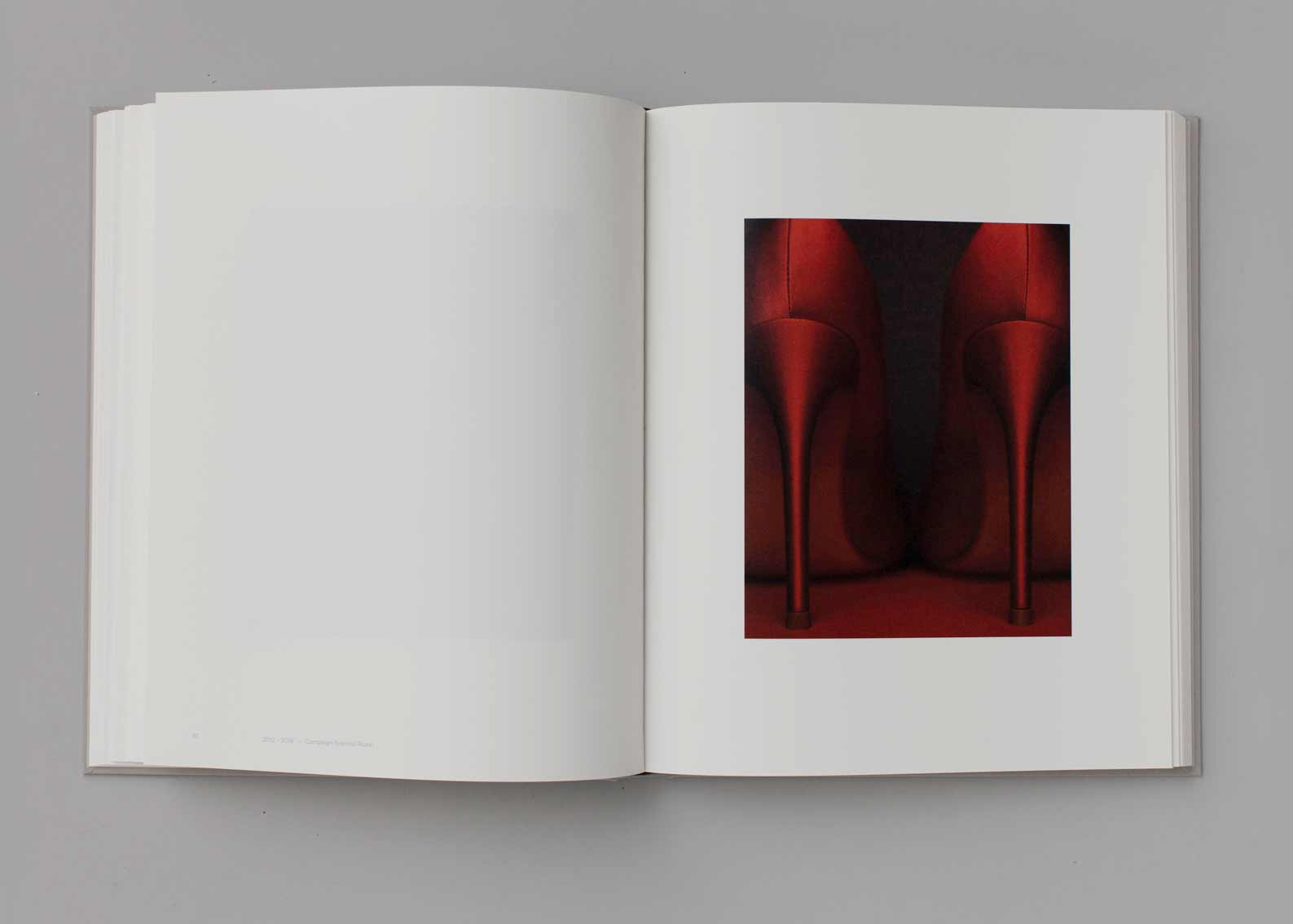

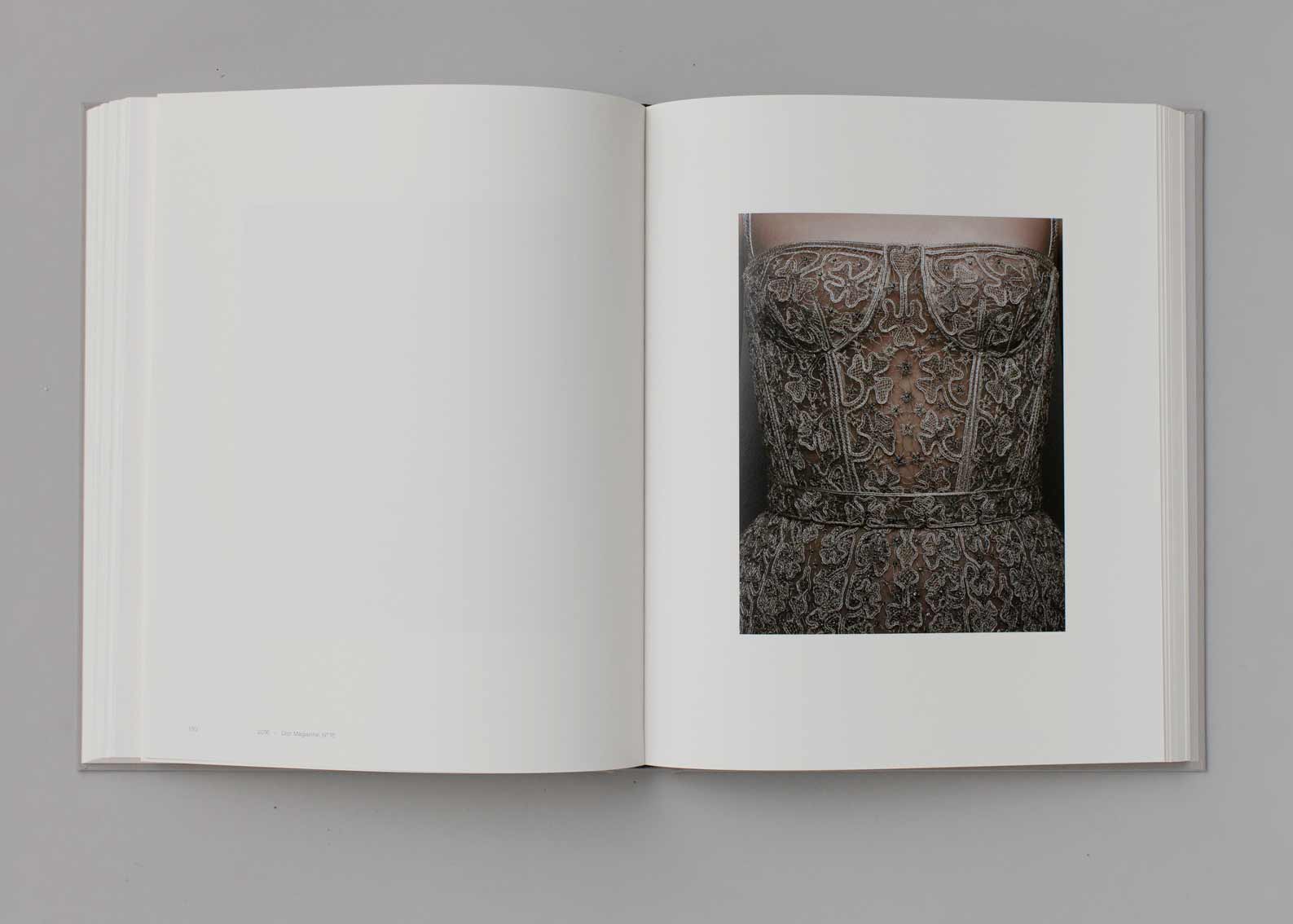

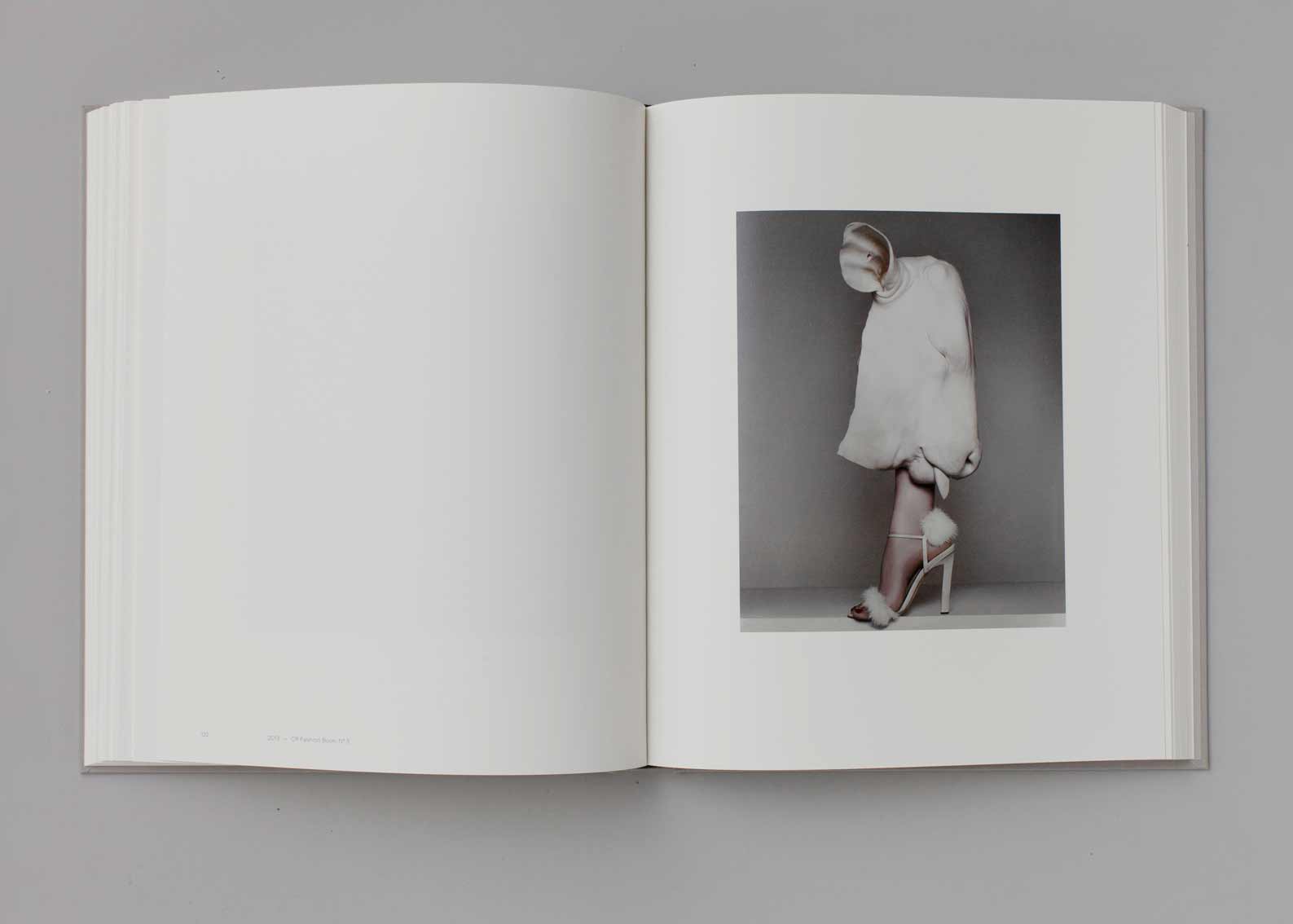

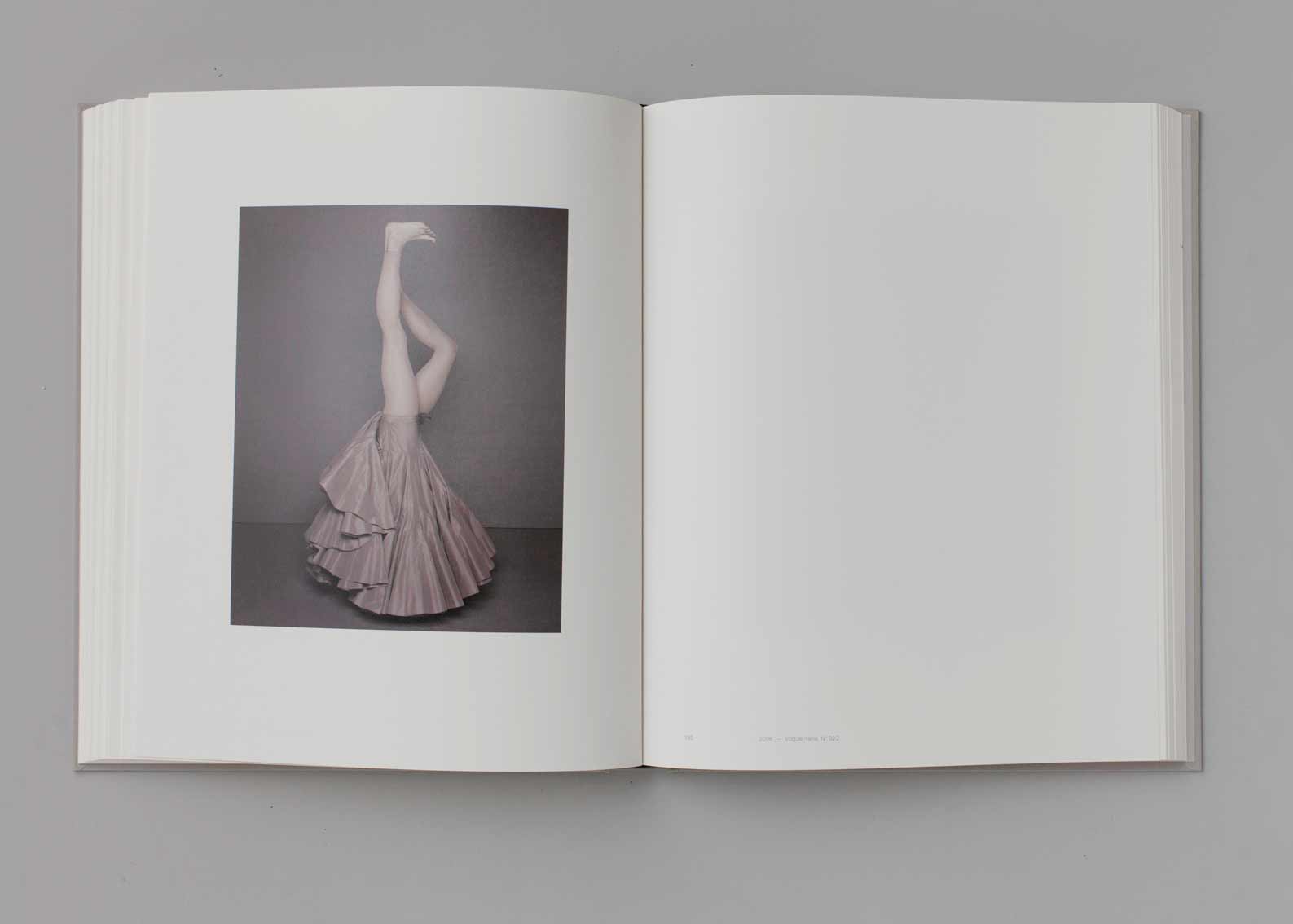

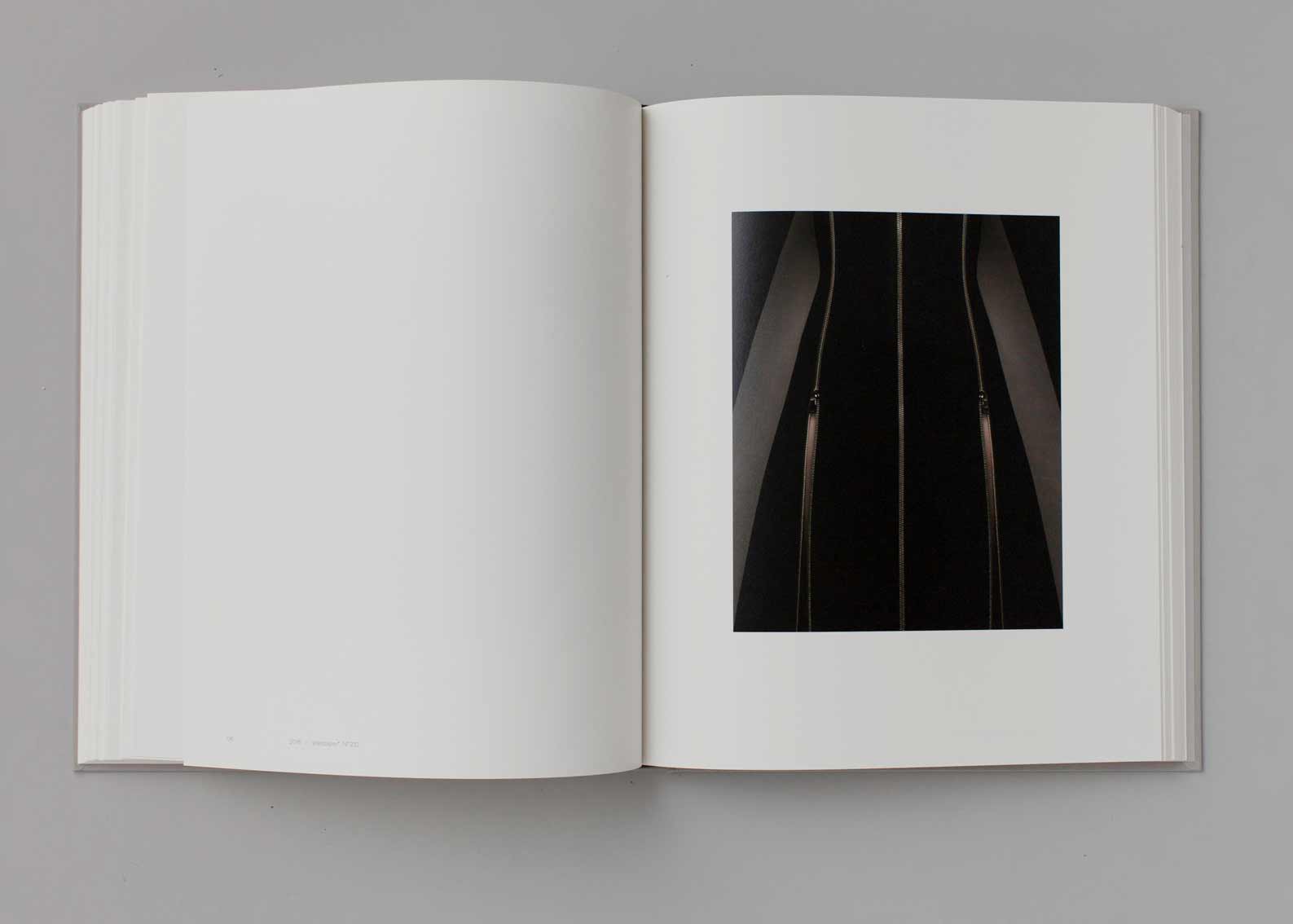

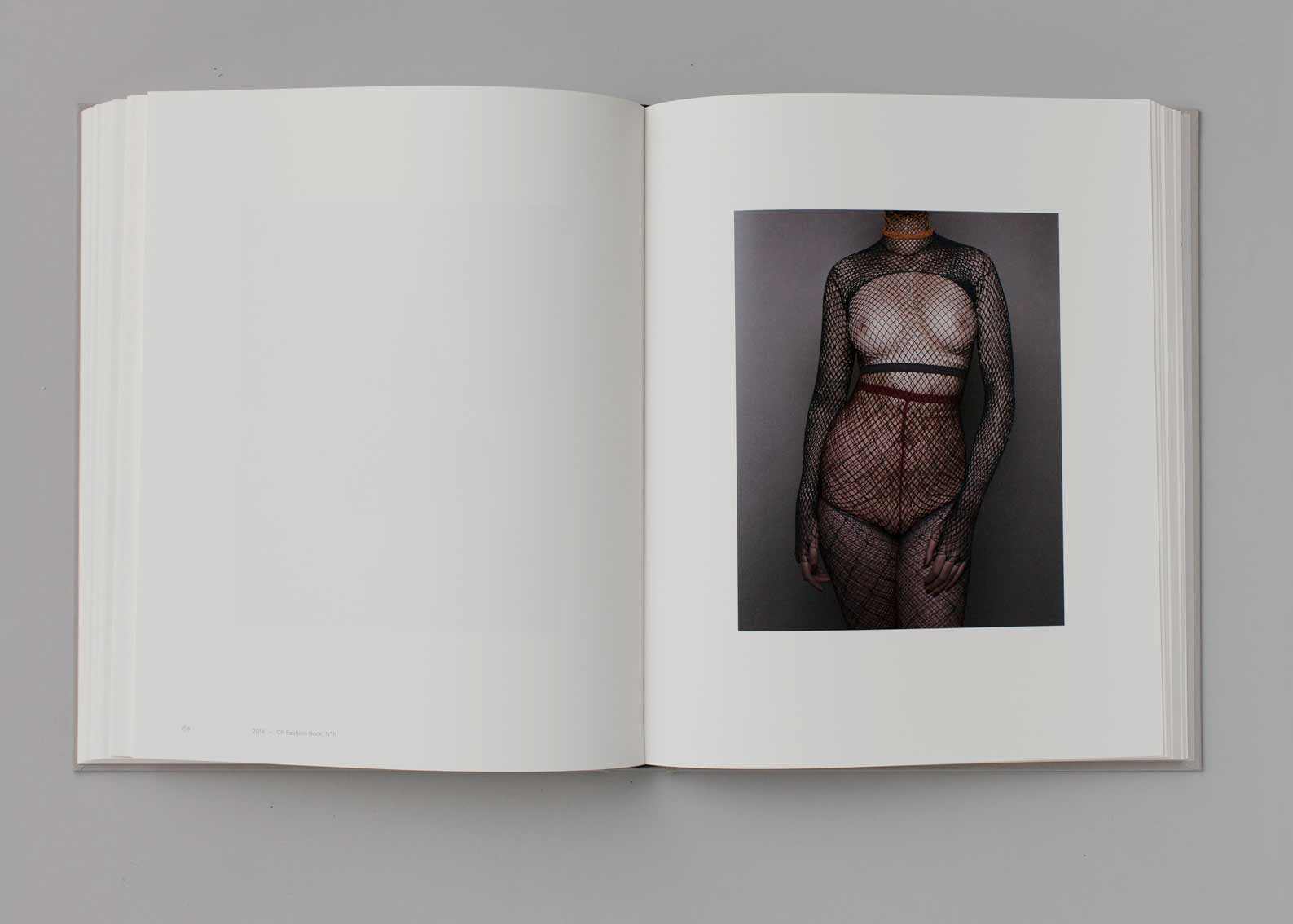

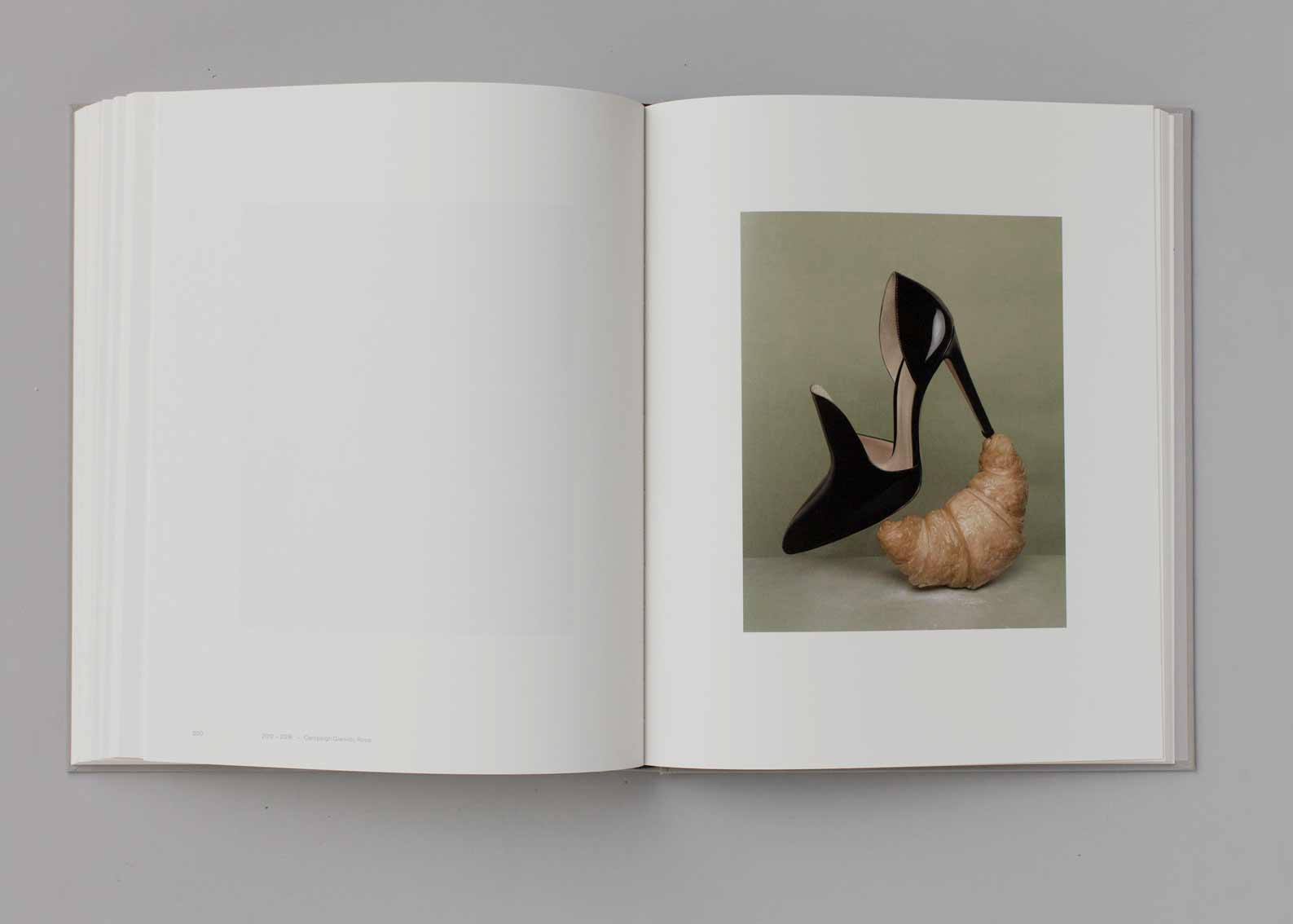

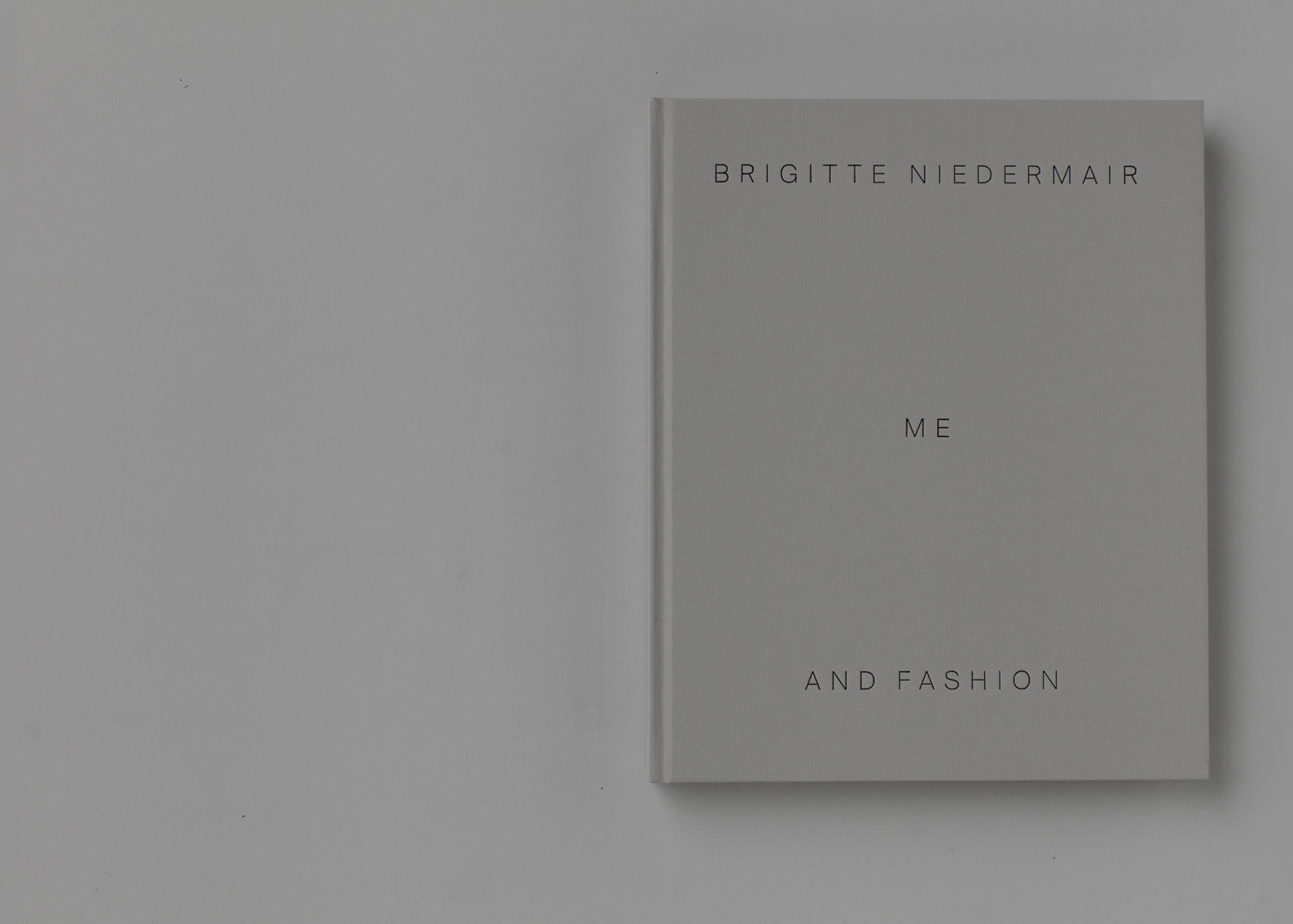

ME AND FASHION

ME AND FASHION

2019

278 pages

Damiani

33 x 27,3 cm

ISBN 9788862086790